These Four Riders Seem to think so…

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Ed March Malaysia to England |

Sean Dillon Alaska to Argentina |

Matt Terry England to Hell and back |

Antonia Bolingbroke Kent Ho Chi Minh Trail |

The story of the Cub

We look back at how it all began. Keep an eye out for the bits in bold to see if lessons can be learned for the future…

The year was 1956 and Soichiro Honda and Co-Founder Fujisawa had left for Europe on what they called an observation tour. On the flight, the two men debated what Honda’s next product should be. Soichiro favoured a scooter, while Fujisawa favoured a moped. At the time, two-stroke mopeds were extremely popular in Europe, where they were a convenient mode of transportation that didn’t require a license. As Soichiro listened to Fujisawa, he gradually warmed to the idea of a moped.

When the two men arrived, they immediately went looking for the mopeds that were currently being produced all over Europe, but none of them really matched the idea of the product Honda wanted to make. Soichiro remarked to Fujisawa, ‘These bikes are designed for Europe’s well-built roads, but they simply aren’t appropriate to Japan. If we want to make a bike with minimum horsepower that’s a pleasure to drive in Japan, it really needs to have a four-stroke engine.” The two men headed back to Japan with burgeoning dreams of a new kind of motorcycle.

By the time Soichiro returned to Japan, he already had an image in his mind of the new product he wanted to make. It incorporated Fujisawa’s idea of creating a small bike that would expand Honda’s customer base, plus a low-floor, step-through design that would make it easy for women to ride, too. Soichiro insisted on a four-stroke engine.

In early 1957, Honda began work on the vehicle’s engine. It was the first time anyone in the world had attempted to mass-produce a 50cc OHV 4-stroke engine, and the development team came up with more and more ideas that flew in the face of conventional wisdom. Ultimately, they created an engine with ‘phenomenal power’: 9,500 rpm and 4.5 horsepower!

At the same time, Honda began to develop the Super Cub’s automatic centrifugal clutch. The goal was to produce a bike that could be operated one-handed, as at the time soba restaurant deliveries were made by bicycle riders carrying boxes with their right hand, whilst steering with their left. This turned out to be extremely challenging, however, with difficulties associated with disengagement during shifting and the revolution ratio of the kick starter. The result was the birth of the revolutionary automatic centrifugal clutch.

Soichiro was very particular about the size of the tyres. The bike had to handle well on Japan’s unpaved roads, but it also had to be compact. Honda decided that the ideal tyre size would be 17-inches, a size that did not yet exist for production vehicles. The major tyre manufacturers all refused to produce a new tyre size for just one model, but after numerous rejections, Honda finally located a small manufacturer who was willing to do it.

On December 24, one year after development had begun, the final FRP mockup was completed. The intricate mockup was mounted on a table top in the cafeteria, and as they stood in front of it, Soichiro asked Fujisawa, “Senior Managing Director, how many of these do you think we can sell?” Without missing a beat, Fujisawa responded, “30,000 units!” Astonished, the other associates exclaimed, “30,000 units a year?” When Fujisawa responded “No, 30,000 units a month!”, everyone was stunned.

On December 24, one year after development had begun, the final FRP mockup was completed. The intricate mockup was mounted on a table top in the cafeteria, and as they stood in front of it, Soichiro asked Fujisawa, “Senior Managing Director, how many of these do you think we can sell?” Without missing a beat, Fujisawa responded, “30,000 units!” Astonished, the other associates exclaimed, “30,000 units a year?” When Fujisawa responded “No, 30,000 units a month!”, everyone was stunned.

At the time, the total number of motorcycles sold each month in Japan was only around 40,000 units, and besides, Honda did not yet have the production capacity to produce 30,000 units per month. Fujisawa, however, was already envisioning the blueprints for a new factory that would be built to accommodate production of the new motorcycle.

To make the new motorcycle, Honda built a new ¥10 billion factory in Suzuka Mie, manufacturing 30,000, and with two shifts, 50,000, Super Cubs per month. The factory was modelled on the Volkswagen Beetle production line in Wolfsburg, Germany. Until then, Honda’s top models had sold only 2,000 to 3,000 per month, so it was a massive gamble for Honda to take. When completed in 1960, the Suzuka Factory was the largest motorcycle factory in the world. The economies of scale achieved at Suzuka cut 18% from the cost of producing each Super Cub when Suzuka could be run at full capacity.

To make the new motorcycle, Honda built a new ¥10 billion factory in Suzuka Mie, manufacturing 30,000, and with two shifts, 50,000, Super Cubs per month. The factory was modelled on the Volkswagen Beetle production line in Wolfsburg, Germany. Until then, Honda’s top models had sold only 2,000 to 3,000 per month, so it was a massive gamble for Honda to take. When completed in 1960, the Suzuka Factory was the largest motorcycle factory in the world. The economies of scale achieved at Suzuka cut 18% from the cost of producing each Super Cub when Suzuka could be run at full capacity.

When the Super Cub C100 hit the market, it was priced at 55,000 yen, an amount well within the reach of the ordinary consumer, but challenging profitability-wise. Still, Fujisawa was determined to set a price that was attractive to the average person to expand the customer base. Meanwhile, during development, Soichiro insisted, “I want you to make the best product possible, regardless of cost. We can make up for the cost in mass production.” Along with his high standards in manufacturing quality, Soichiro clearly had a lot of confidence in Fujisawa’s abilities as a salesman.

Fujisawa came through with a sales strategy full of novel ideas. First, they would need to build a retail network. Fujisawa put the word out via a mass mailing, contacting businesses with strong community roots that until then had nothing to do with motorcycles, such as lumber dealers and grocery stores.

Fujisawa came through with a sales strategy full of novel ideas. First, they would need to build a retail network. Fujisawa put the word out via a mass mailing, contacting businesses with strong community roots that until then had nothing to do with motorcycles, such as lumber dealers and grocery stores.

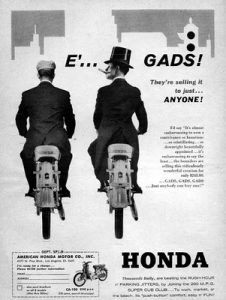

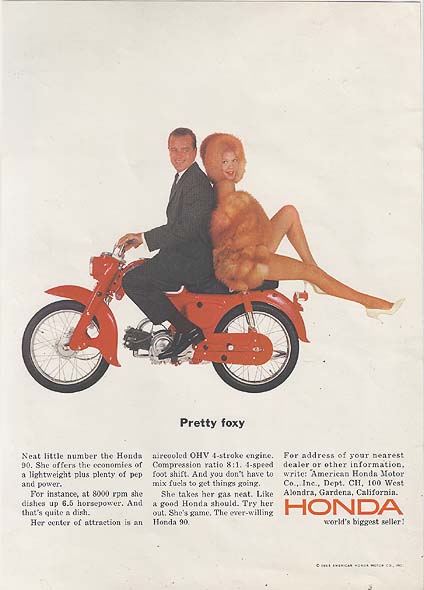

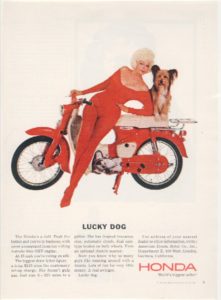

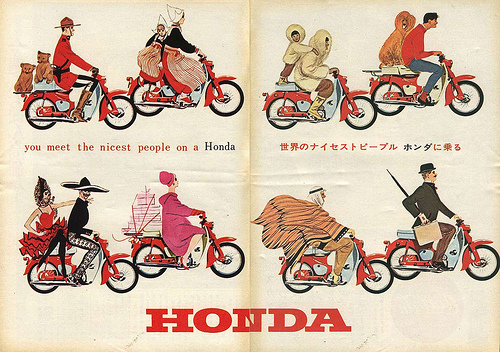

He created a network of shops where women would feel comfortable shopping, and in 1960 he began running ads in general-interest magazines.

At the time, it was unheard of to advertise motorcycles in anything other than specialized motorcycle publications.

These efforts to expand Honda’s customer base were astonishingly effective, and in just a few years, Fujisawa’s unbelievable projection of 30,000 units per month had become a reality.

At the heart of the bike’s success was the pressed steel monocoque chassis, with the horizontal engine placed below the central spine, a configuration now called the ‘step through’ or ‘underbone’ motorcycle. Unlike a scooter, the engine and gearbox unit was not fixed to the rear axle. This had several benefits. It moved the engine down and away from the seat, detaching the rear swingarm motion from the drivetrain for lower unsprung weight, and also made engine cooling airflow more direct. Placing the engine in the centre of the frame, rather than close to the rear wheel, gave it proper front-rear balance.

At the heart of the bike’s success was the pressed steel monocoque chassis, with the horizontal engine placed below the central spine, a configuration now called the ‘step through’ or ‘underbone’ motorcycle. Unlike a scooter, the engine and gearbox unit was not fixed to the rear axle. This had several benefits. It moved the engine down and away from the seat, detaching the rear swingarm motion from the drivetrain for lower unsprung weight, and also made engine cooling airflow more direct. Placing the engine in the centre of the frame, rather than close to the rear wheel, gave it proper front-rear balance.

The original pushrod overhead valve (OHV) air-cooled four-stroke single-cylinder engine had a 40-by-39-millimetre (1.6in × 1.5in) bore × stroke, displacing 49 cubic centimetres (3.0 cu inch), and could produce 3.4 kilowatts (4.5hp) @ 9,500rpm, for maximum speed of 69km/h (43mph). The low compression ratio meant the engine could consume inexpensive and commonly available low octane fuel, as well as minimising the effort to kick start the engine. Unlike many scooter CVTs, the centrifugal clutch made it possible to push start the Super Cub.

The early Super Cubs used a 6 volt ignition magneto mounted on the flywheel, with a battery to help maintain power to the lights, while later ones were upgraded to capacitor discharge ignition (CDI) systems. The lubrication system did not use an oil pump or oil filter but was a primitive splash-fed system for both the crankcase and gearbox, with a non-consumable screen strainer to collected debris in the engine oil.

Specific elements of the Super Cub’s design were integral to the campaign, such as the enclosed chain that kept chain lubricant from being flung on the rider’s clothing, and the leg shield that similarly blocked road debris and hid the engine, and the convenience of the semi-automatic transmission. Presenting the Super Cub as a consumer appliance not requiring mechanical aptitude and an identity change into ‘a motorcyclist’, or worse, ‘a biker’.

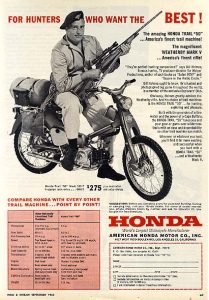

But American Honda’s Cub sales proved lacklustre. The US market was dominated by motorcycles of at least 500cc displacement, and the pervading image of motorcycles was ‘rough and dangerous.’ Despite this, they designed a Mini-Trail and other new models that catered to the US market and used the mass mailing strategy to expand their sales network to sports equipment and fishing gear retailers, establishing a sporty image for the brand.

In 1960, Jack McCormack (first national sales manager of American Honda Motor Company) noticed that one Honda dealer in Boise, Idaho was selling more Honda 50s than the combined total of all six dealers in Los Angeles. He found out that the Idaho dealer, Herb Uhl, was selling the CA100s as a trail bike by adding knobbly tyres for off-road traction and increasing the final drive by using a larger rear sprocket with more teeth. Uhl said the advantages of lightweight and the automatic clutch allowed unskilled riders to enjoy off-road riding, in comparison to traditional big trail bikes that could be difficult to handle. McCormack shipped a version of Uhl’s customised CA100 to Japan and requested Honda put it into production, and by March 1961 it was available to US dealers.

Today, fifty years since its birth, the Cub’s market continues to expand while its design remains fundamentally unchanged. Each year, close to 5 million units are produced worldwide. The Cub is truly a global standard, reaching production volumes unrivalled in the history of motorised transportation. While styling and other details vary slightly by location and application, the Super Cub has always retained its identity as a useful vehicle that is easy for anyone to ride.

Following the trail of bold text, it’s possible to suggest that the problems facing the motorcycle industry today are no different to those of sixty years ago. What we need perhaps is another ‘Cub’, whoever happens to build it.

In The Classifieds

Honda C90s are fetching good money these days, aided by the drop in number of the old and tatty ones, and the rising availability of well cared for, low mileage pristine examples. Expect to pay upwards of £400 for a tatty one, and getting on for £2,000 for a mint late model with low miles (whether anyone pays that is another matter).

Honda C90s are fetching good money these days, aided by the drop in number of the old and tatty ones, and the rising availability of well cared for, low mileage pristine examples. Expect to pay upwards of £400 for a tatty one, and getting on for £2,000 for a mint late model with low miles (whether anyone pays that is another matter).

The one pictured is a 1988 model with 21,000 miles on the clock for £1,000. Prices will only keep on rising.

ED MARCH

From Malaysia to England

Distance: 14,500 Miles

How long did it take? 8 months

What problems? Several engine meltdowns

The trip was from November 2011 to June 2012. I did it because someone set me the challenge and said that it can’t be done. At the time I’d never been out of Europe, but I wanted to see the world, so I posted my bike to Malaysia and rode it home from there. It didn’t go exactly to plan; when I landed and went to customs to pick up my bike I realised that I’d left my keys at home, so had to hot wire the bike, and then from there just start riding. The first day was mental. There was a real bizarre moment where I came out of the airport and had to stop to work out what side of the road I was supposed to be driving on. But it’s that moment where you stop, and you’re thinking, right, 99% of people are going that way, so I drive on the left!

After two or three hours of riding or so I stopped again at this cafe, looking at my bike, in this amazing scenery, and it was that moment when I realised, ‘I’m in Malaysia, with my motorcycle, I’m here, I have no other purpose than to ride home. This is mental. That’s my bike. I’m not on holiday. I’m not going home in a week. I’ve actually got to ride that back!’ At the time I knew the countries I would go through, but I didn’t know the borders I would cross. I was supposed to get a Pakistan visa, but they wouldn’t give me one. I waited twelve weeks to try and get it, but in the end had to go from Mumbai to Dubai, then into Iran by ferry.

Dubai was absolutely mental, but when you go from India to Dubai it’s ridiculous. In India I filmed 14 people going for a shit by the side of the road, then you go to Dubai where every form of public transport is millimetre perfect. It’s spotless. But it’s a very fake country though, there’s not much soul.

The hardest part of the journey was India. That’s when I felt really low, and the only place I fell ill. It was also the only place I almost got killed on multiple occassions. I’d be stopped at traffic times and people would just ride into the side of me. That can be quite funny, but when you extend that level of incompetence to everything, such as when they fill up your bike they pour petrol over everything, or when you order some food and they trip and throw it all over the floor. I was there four weeks in total. Some people say you obviously didn’t see much of India as you only saw the bad bits, but I did 1,500 miles through it. You can do 100 miles through Belgium and you know what Belgium is like. In the end the trip was 14,500 miles. But I took a detour through Vietnam. It’s about 8,000 miles as the crow flies.

I had a few problems along the way. In Thailand I accidentally had the oil changed for brake fluid. As the mechanic was putting it in I said that it didn’t look like oil, more like water. 100 miles later the piston melted. Physically melted. It was still running but had physically turned itself into an oil pump. It was pumping the oil straight out of the exhaust. No one within ten miles could see where they were driving for the smoke. But I got a full engine rebuild, in a Honda dealership; barrel, piston, rings, gaskets, carb rebuild, spark plugs, oil change and lunch, and that included labour, all for £28. It was one of those brilliant moments where it was, ‘I don’t care how many people are going to take the piss out of my bike, I’ve just got a full rebuild for £28, and I’m doing 45mph, and everything’s okay.

I didn’t do any modifications for the trip. The chain and sprocket lasted me the whole way. I changed the oil every 1,500 miles. I got a new tyre in Bulgaria, having almost made it back on the original, but was given a new one for free. I carried spare electrics, so spare generator, coil, CDI unit, and spark plug and some tools. In Germany, there was a tapping noise in the engine, that turned out to be the shoe on the end of the cam chain tensioner, which we’d bodged together from an old Yamaha foot peg rubber. In Bulgaria, it was making the noise.

After another 1,500 what happened very quickly was that the footpeg rubber disintegrated very quickly, entered the oil pump, jammed the oil pump, and I rode it for another 1,500 with no oil pump. That was when the engine turned gold, and actually melted the plastics around the engine. It had seized and eaten all the teeth on the oil pump. We welded some more on, that failed, then we fitted new parts in Germany and took it around the Nurburgring.

It was amazing, but it was just one of those things, over eight months it becomes the norm. It’s weird, you don’t actually notice freedom whilst you’ve got it. And then you get back home, go back to work and realise the freedom you once had, and you just want it back again…

MATT TERRY

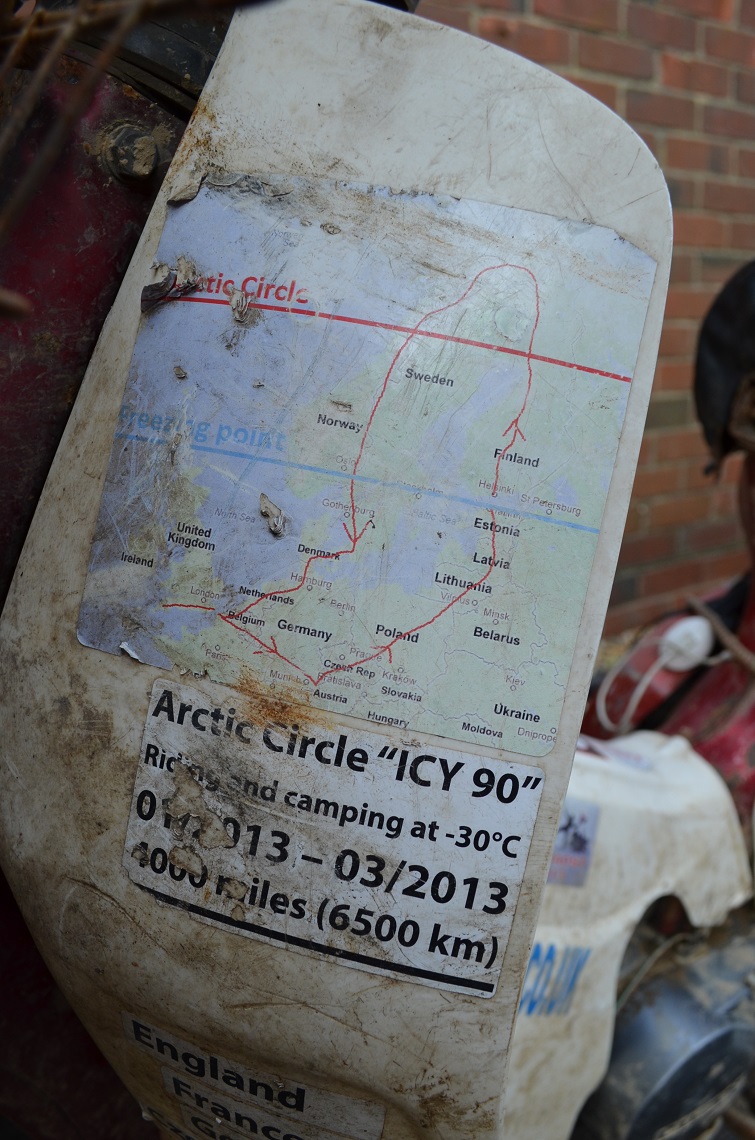

To the Arctic Circle in winter

Distance: 3,500 miles

How long did it take? 1 Month

What problems? Seized rear brake, wheel bearings collapsed

‘Turn back, the weather is impossible.’ It doesn’t matter how old I get, the chance for a motivational text from my mum is always bound to inspire! This one came as I rolled into Dover ferry terminal, the cars beside me queued with their engines running for heat whilst I just sat stationary on the bike and relaxed into the cold as snowflakes settled on my two jackets, giving me the proportions of some bizarre corpulent garden gnome.

Officially my journey was from the Ace Café, London to Hell in Norway, 2,500 kilometres away. I was doing it in aid of Cancer Research having recently seen a friend sit down and explain to his daughters the details of his cancer operation. I needed to do something to stop me feeling so helpless about it all.

I wanted a journey that was just bonkers enough and hard enough that it might encourage people to donate to Cancer Research, as personally I found myself a little donation fatigued. Social media has armed the masses with a weapon to demand money for noble causes with bold claims that they would run 5 kilometres in just three hours, give up wine for a week or some other tripe. Yes I’m a cynical and jaded old bugger, but the fact is I’m not alone in thinking like that. I donate when I want to, to whom I choose regardless, if you want me to sponsor you, you need to impress me!

So I’d set my own standard, I would underwrite the cost of the trip and set some conditions, such as no payment for accommodation or hot meals, all wasted money that should go to the charity I was raising cash for. I needed it to be hard, I wasn’t disappointed!

I hadn’t expected snow from the very beginning and so the news that Britain was ‘shut down by severe weather’ wasn’t a good start, especially having crashed, bust up my knee and lost my tent just getting to the start of the event from my home in Cornwall.

Initially, even the autoroutes were snowbound, and this far south there were no plough drivers working on a Sunday night and so getting out of France was a tough stint into driving snow, followed by a night without a tent, sleeping in a bivi bag behind the bins of a Belgian service station. Pressing on I found a mixture of great places to camp and great people wanting to put me up and to help me fix my lack of tent problem as I continued north.

I got to speak to a few policemen and women as I crossed Europe; concerned citizens reporting some Englishman riding a moped up the autobahn. They had a point; on one occasion the C90 jumped out of third gear into second just as I went to join the ‘Bahn and joining the autobahn at 20mph is not advised! On another occasion, somewhere near Hanover, I was camped in a layby and the police came trudging through the snow just to check I was alive. They seemed pleasantly surprised that I was, which was rather sweet.

The advantages

Its light, which combined with a low seat height make it pretty easy to physically move about or get back into shape when needed. It makes less power than a ride-on lawnmower, not so good when you are trying to get across Germany via the autobahn, but perfect for finding traction on slippery surfaces. It’s cheap to buy and to run, and being such a globally prevalent model parts are pocket money to buy. It doesn’t need a battery to work, and it’s a breeze to kickstart.

—

The disadvantages

It’s slow. Between the UK and Norway, I stopped counting how many people tried to overtake me in my lane or force me into the icy hard shoulder, not to mention getting pulled over by the police and accused of riding a 50cc. No large stator means you can leave the heated vest at home, though of course, you should never be reliant on heated gear for warmth, expecting everything to fail except your spirit. The headlamp is abysmal, given a distinct lack of daylight hours the further north you go. I suffered carb icing and the fuel tank is tiny, having to stop every 100 kilometres to refuel.

—

Mods

I fitted handguards, I also had different spark plugs for extended high rpm running and cold conditions, I took advice on oil and found something that would solidify at a much lower temp than stock, but being fully synthetic it burnt off a little on the old motor. I also had a spare 10-litres of fuel. It wasn’t often needed but I was glad of it despite the weight penalty. The mudguards were cut to accommodate larger knobbly tyres.

The truth is the tougher it got the happier it made me. I was ill-equipped for the conditions (I could have thrown money at the problem, well if I had any, but I was pushing my luck). A yard jacket from a builders yard, snow boots costing a tenner from a discount online sports retailer, big-budget it was not, a big adventure it certainly was!

By the time I turned off up Norway’s cold East valley (the Osterdalen) I had some serious doubts about how many toes I’d come back with. I reassured myself that the sharp stabbing pain in my feet was a good sign I wasn’t yet frostbitten, or that I was still shivering meant that my body was not yet hypothermic. I piled in calories wherever possible; chocolate, nuts and other things that wouldn’t freeze solid, I still dropped over a stone in my short time away.

But it was also a truly beautiful experience. I’ll never forget riding my bike into a moonlit forest to camp, the snow shone like a diamond-encrusted blanket of pure white to mirror its obsidian counterpart above me.

Or being the only vehicle braving an unploughed section of track for several hours, in the company of majestic mountains guarded by the sentinels of thick pine forest, frozen waterfalls lined the roadside like some monochrome of a giant chocolate fountain captured in a photo.

Having made it to Hell, the bike was laid up in Norway for the winter, and the motor easily kicked into life six months later. Okay, so the rear drum brake had seized and the pad had come off the shoe, and a little later on my rear wheel bearings collapsed (I found out they are unsealed bearings the hard way) but ultimately £30 in parts was all it took to ensure the tough little Honda got me all the way home the next June, I smile each time I see it now, we share a secret history that most of the world is oblivious to.

On the return leg we even managed a 690-mile day between Flensburg and Brugge, plus a man at a petrol station in Holland dropped to his knees and waved in prayer ‘we are not worthy, we are not worthy’ that’s never happened to me on my KTM Adventure!

If you’d like to know more feel free to contact me – Stickysidedown through the magazine’s own forum.

SEAN DILLON

From Alaska to Argentina

Distance: 33,000 miles

How long did it take? 2 years

What problems? Dealing with altitude issues at 5,700 metres

Having thrashed my bike all the way from Alaska to Argentina covering more than 30,000 miles over the course of two years I can say a few sure things about the Honda C90. And one thing for sure is that this bike is unstoppable! When Soichiro Honda said he wanted to build a ‘go anywhere’ bike he certainly succeeded with the Honda Cub, and while you will almost certainly always gets there, you will never get there that fast.

So why the Honda C90 for my 30,000 mile trip from Alaska to Argentina? I have had a long, long, affair with the Honda Cub and when dreaming up my plan to take it across the world I had not heard of others doing such a thing, and as far as I was concerned I was the only stupid person to attempt such a pointless deed. That aside, the bike symbolised a lot about the journey I was about to undertake.

■ Widened legs shields – useful from keeping rocks from smashing your legs on Ruta 40, also useful for keeping the wind and rain off .

—

■ USB charger – keeps my phone and GoPro juiced up.

—

■ Sexy front basket – do not underestimate the power of the sexy front basket, despite doing no favours whatsoever to my masculinity. It has proven its worth when carrying my food upfront in a cool bag. It has also helped me score birds as I’ve been told a man with a front basket is very non-threatening. I know; who would have thought, eh!

—

■ Single saddle mod. – made for ease of refuelling. The saddle being donated to me by none other than Patrick Hemingway, Ernest’s Grandson when I stayed with him in Vancouver.

—

■ Extra fuel capacity – The standard tank only being 3.5-litre posed a bit of a problem, but getting up to 115 miles from one tank you can go surprisingly far on one tank. However, I carry a 10-litre plastic rum bottle between my legs. This gives me a range of up to 500 miles depending on altitude, wind, fuel quality and generally her mood on any given day. Never be afraid of carrying explosive liquids near your crotch.

—

■ Luggage – I adapted a rack system to carry Givi soft panniers and a top bag, which has worked very well. I also have a Rickman backbox.

—

■ Working at altitude – when in extreme altitude a #72 main jet worked extremely well. At 5,700m above sea level on the side of a volcano in Chile it still worked like a dream. A 13 tooth front sprocket was also very useful for some of the extreme climbs. Crossing rivers was never an issue, the air filter is located about 1.5m off the ground. Though the exhaust is fully submerged it doesn’t seem to mind. It just blows bubbles.

I wanted simplicity and I wanted to meet people. I knew I was going through some poor countries and I didn’t want to set myself apart, I wanted to blend in. I figured a large expensive bike would put up this invisible barrier between me and many of the people I would end up meeting on my journey, possibly restricting my interactions. And it seemed to work, as I spent a lot of time accepting offers of generosity across the Americas. And when I say generosity what I mean really is having genuine cultural exchanges. Which is why you travel, right?

I avoided hostels and hotels as much as I could when travelling by myself and I found that the little bike provided me with many opportunities to meet new people. In hindsight, the interactions may have been out of simple pity for me due to my unfortunate choice of motorcycle, but I am ok with that too!

I set myself and the bike many challenges on the trip; heading into the Arctic on the infamous Haul Road In Alaska, driving the great Salt Plains of Bolivia, tackling the Death Road, the Carretera Austral in Chile, Ruta 40 in Argentina and of course the pinnacle of the little bikes achievement; setting a record for the highest ever Honda Cub.

This little adventure took place over four days on the side of a volcano in Chile where myself, my brother Gavin and Canadian friend Gordon armed with a shovel, rope and some Viagra (ahem.. for medical reasons) headed off on an expedition where we would climb along some snowy hiking trails to reach an altitude of 5,706m above sea level with the bike.

|

|

|

|---|

A full 100 metres higher than the highest road in the world in Tibet, thus cementing El Burrito’s (the little donkey) position as the highest ever Honda Cub.

If you are looking for an overland machine this may be for you. It will certainly get you there and provide many good times along the way. However, if you want to do an extended trip you will inevitably end up on some long fast roads and being the slowest thing on the road is never a good idea, but if your journey is made out of love for the machine and seeking good fun and interaction, then why not!

ANTONIA BOLINGBROKE KENT

Along the Ho Chi Minh Trail

Distance: 2,000 miles

How long did it take? 6 weeks

What problems? Four engine rebuilds!

At some point a few years ago I decided it was time for a proper adventure, the sort where I’d find myself deep in the Southeast Asian jungle; alone, slightly terrified and knee-deep in mud. So in the spring of 2013, after months of wondering what the hell I’d let myself in for, I headed east for a solo motorcycle journey down the legendary Ho Chi Minh Trail.

While scores of travellers ride a tourist-friendly, tarmac version of the trail between Vietnam’s two major cities, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, only a handful follow its gnarly guts over the Truong Son Mountains into Laos. Even fewer trace it south into the wild eastern reaches of Cambodia. I wanted to do both.

For two months I’d be riding alone through some of the remotest terrain in Asia, through jungles that hid both a deadly legacy of unexploded bombs and an alarming array of deadly beasts. There’d be mud and mountains, lonely forested tracks and – in many areas – no humans for miles if anything went badly wrong. I was excited and terrified in equal measures.

In my eyes, there was only one motorcycle fit for such a trip: the Honda Cub, the workhorse of Southeast Asia. With three gears, an automatic clutch, slender city wheels and brakes that would barely stop a bolting snail, the humble Clunk wouldn’t be everyone’s first choice.

But with my meagre budget, limited mechanical know-how and lack of off-roading experience, the cheap, light, idiot-proof Cub suited me perfectly. Not only are they fixable with a spanner and some gaffer tape but you could leave a Cub in a ditch for five years, trample on it with an elephant or two, fill it with chip fat and it would still start. Discovery Channel weren’t wrong when they voted it the greatest motorcycle ever made in 2006. My particular model, a 25-year old pink beauty dubbed the Pink Panther, was sourced and pimped for me by Hanoi motorbike tour company Explore Indochina and cost a mere $350.

The Vietnam War began on the 1st November 1955 and lasted almost twenty years. Throughout the war, the Ho Chi Minh Trail was a network of trails and tracks used by the North Vietnamese as a means of getting its troops and supplies down into the South in order to help the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam fight the United States. It was then a secret supply network, that often crossed into Laos and Cambodia and was repeatedly targeted and attacked by the United States, often by means of defoliants – the most famous being Agent Orange – used to kill off the greenery that gave cover along the trail. Attempts by the Americans to wipe out the trail were never successful. In total the ‘trail’ was about 1,000 kilometres in length and consisted of many strands and arteries. Today it’s a difficult trail to follow, with no clear mapping and much of the jungle route cleared through de-forestation.

—

There were other reasons behind my choice of vehicle. My route would pass through some of the poorest parts of Asia, mountainous tribal lands where the sight of a foreigner was still an extreme rarity. Some of the people here lived in medieval conditions, in bamboo villages absent of schools, sanitation, electricity or material wealth. My white face and motorbike gear were going to be enough of a shock: I hoped that riding a cheap, familiar bike might fractionally lessen the cultural chasm between us. Finally, doing it on a proper dirt bike seemed too easy. There was infinitely more comedy value in attempting to trundle down the trail on an antiquated, pink Cub.

For the first thousand miles the Pink Panther whirred contentedly south, her wheels spinning over Vietnamese tarmac and crunching happily over the bone-dry dirt of Laos.

But halfway – after weeks of forcing her through deep mud, over jagged rocks, across a myriad of rivers and up steep mountainsides – she started to struggle. Her engine rattled and sputtered like a bronchitic tractor until, one fateful morning in deepest Laos, it choked, rattled once more and finally died. A chain-smoking, tattooed local mechanic quickly diagnosed the problem: the cam chain and sprockets had gone, in turn damaging the valves and cylinder barrel. The next day, after a £25 engine rebuild, we were back in action. Things would have been very different had I been on a flashy new-fangled machine.

By the time I reached Ho Chi Minh City the incident had been repeated three more times. It was hard to fathom why the same thing kept happening over and over again. It could have been due to poor quality parts, or each mechanic setting the cam timing wrong. Or maybe it was simply that my indestructible Cub couldn’t cope with the rigours of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. I never held Panther’s misdemeanours against her.

She was my friend, and occasional foe, over those long mountains and having the odd breakdown was part of the adventure. As Ted Simon says, ‘the interruptions are the journey’ and these mechanically-enforced pauses offered chances to meet people and hear their stories. It would have taken a lot more to dampen my affections for the Honda Cub – still, in my view, the world’s finest ever motorcycle.

To find out more about Ants’ adventures please see www.theitinerant.co.uk. You can also follow her at @AntsBK.