As the author of the Adventure Motorcycling Handbook, Chris Scott has helped countless bikers pursue their dreams of global travel for almost 30 years by providing practical information and advice on exploring the world. With a new edition published in 2020, James Oxley caught up with the man behind the adventure bikers’ bible

Tell me about your first adventure on a motorcycle?

At that time (1977), I was into climbing and mountain walking, and Snowdonia was surely doable in a long weekend from London on a Honda SS50? It was February so I was hoping to catch some snow on the peaks. Various navigational blunders and fuelling interruptions made me realised that 250 miles at 32.5mph was perhaps a bigger number than I thought. I didn’t even get halfway, but the snow found me.

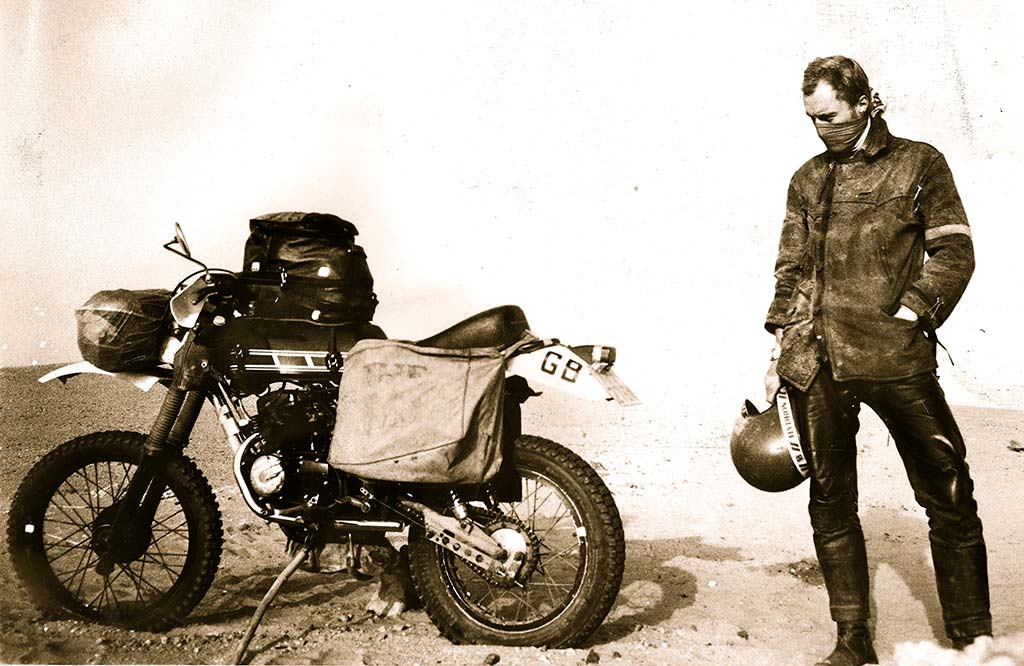

You’re well known for your love of desert travel and the Sahara in particular. What inspired you to take your first journey to the Sahara in 1982, and what impact did it have on you?

By now, I’d discovered trail biking. It was more fun with fewer injuries to bones and licence. But even then, worthwhile trail biking in the South East was a washout, and with no car licence, Welsh enduros were an effort. At the same time, Dirt Bike magazine from the USA was obtainable in specialist Soho newsagents. It regularly featured the wide-open deserts of the western USA. Who wouldn’t rather be there than slithering up some water-logged byway in Surrey? The Mohave was obviously miles away but the Sahara was just over the Mediterranean, which was on the other side of France.

How did these early journeys inspire you to create the first Adventure Motorcycling Handbook?

Initially I enjoyed writing up my desert travels for magazines. Then I discovered Amstrad computers and set about putting what I’d learned over 10 years into Desert Biking, a report for the Royal Geographical Society’s library. Pleased with my results, I thought a travel bookshop in Charing Cross might like to sell copies but they suggested I expand it. A short time later the internet had become a thing so I was able to track down globe-trotting contributors to help fill in the gaps and the Adventure Motorcycling Handbook was born.

How did you set about compiling that first edition from scratch?

Actually, I find it easy and logical. Existing guidebooks, and even a Haynes Manual, have a similar contents structure: research, preparation, execution. I’d learned that from co-authoring Rough Guides’ Australia title. A country breaks down into provinces with cities and towns which have places to stay and eat, and things to see and do. With a number of pages or words, you break it all down, cook up the headings, then fill in the missing words in between.

Is there anything you would have done differently?

You mean with the book? I wouldn’t have waited 30 years to go to full colour, even if this hasn’t been a running complaint among readers. I’d also offer an ebook version. People ask for this all the time but that’s down to the publisher.

Why do you think the Adventure Motorcycling Handbook has proved so popular with motorcyclists for more than a quarter of a century?

I set out to write these guidebooks as if I were a clueless first-timer looking for guidance and inspiration. With Adventure Motorcycling Handbook it also helps that, unlike say a guidebook to France, there’s nothing else like it in English. Adventure Motorcycling Handbook manages to synthesise the experiences of several for the many while avoiding getting too pompous about the whole ‘adventure’ thing.

I also think some readers go on to make mistakes anyway, then realise ‘oh, Adventure Motorcycling Handbook said that would happen’ and the penny drops. Advice can only do so much. The best way to learn is from experience.

How has adventure motorcycling and your travel experiences changed over time, and has that altered the way you approach later editions of the handbook?

My travel experiences or interests haven’t changed that much other than moving with the times, same as everyone else. Has independent global motorcycle travel increased or are we just watching and reading about it more? I think it clearly has along with all tourism and recreation as freedom, and the means to travel has grown.

One thing I’ve become aware of in recent editions, and following online chatter, is that what’s obvious to me and my peers may not be so to all readers. Not everyone grew up repairing rat bikes and so need some things explained more fully.

Are you proud to have coined the term ‘adventure motorcycling’ and how does it feel to have inspired so many people to embark on their own adventures?

Putting two words together which catch on is something writers do once in a while. There are many serendipitous external factors which help make that happen. I do allow myself a brief glow of pleasure on receiving a grateful email, but inspiration is all around. If not the Adventure Motorcycling Handbook, it will be something else. What counts is to be receptive to it and to then, if possible, to act on it.

Did you ever imagine adventure motorcycling would become as popular as it has, not only in terms of more people travelling by motorcycle, but also in terms of the motorcycle and travel industries that have grown around it?

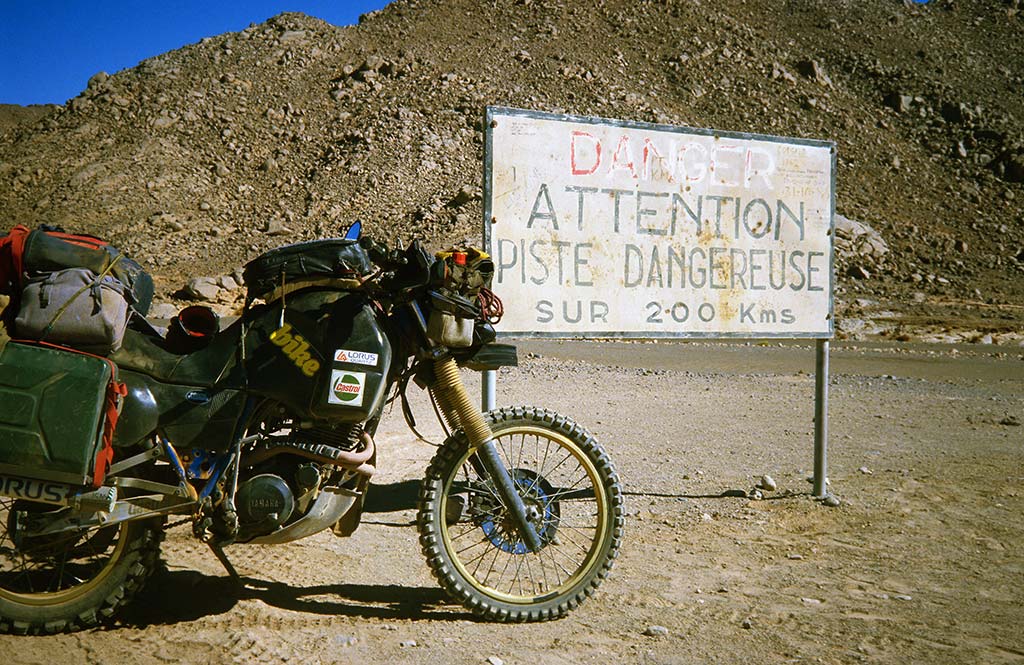

Until last March, tourism and recreation have been booming worldwide and motorcycle travel was a part of that. We can thank a brilliant selection of machines and associated clobber, the advent of GPS and digital mapping, as well as an awareness that what was once thought of as outlandish is easy enough with opportunity and commitment.

The Long Way Round television programme definitely contributed to that boom and many tour operators, gear manufactures, air freight services and so on have benefitted from the dynamic duo’s televised adventures. It helps money and people to slosh around the world.

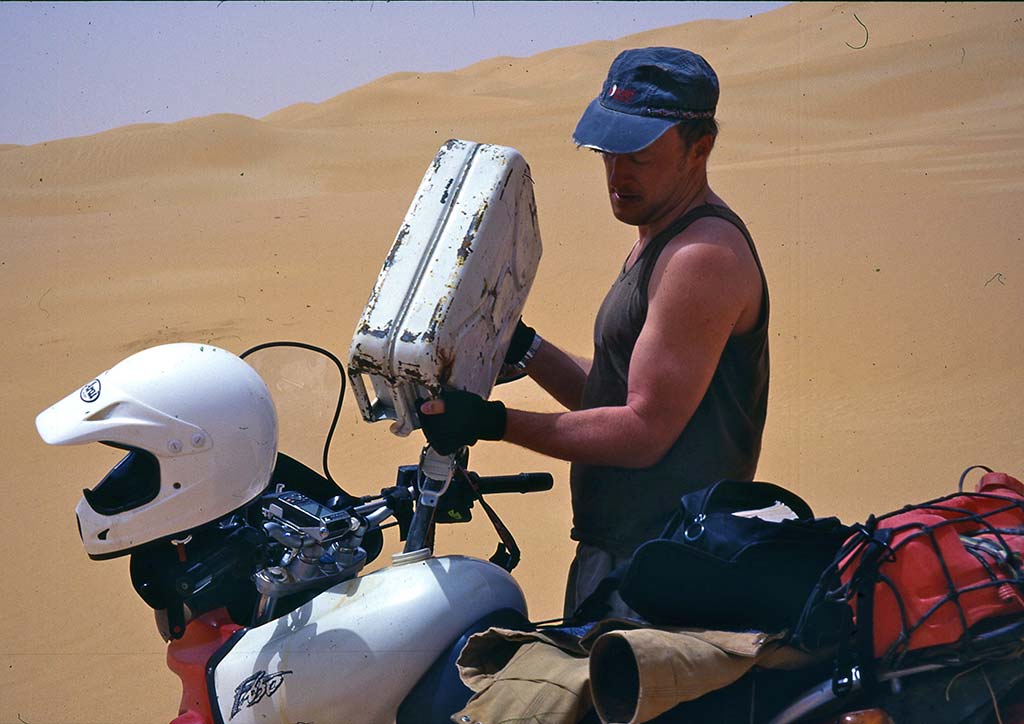

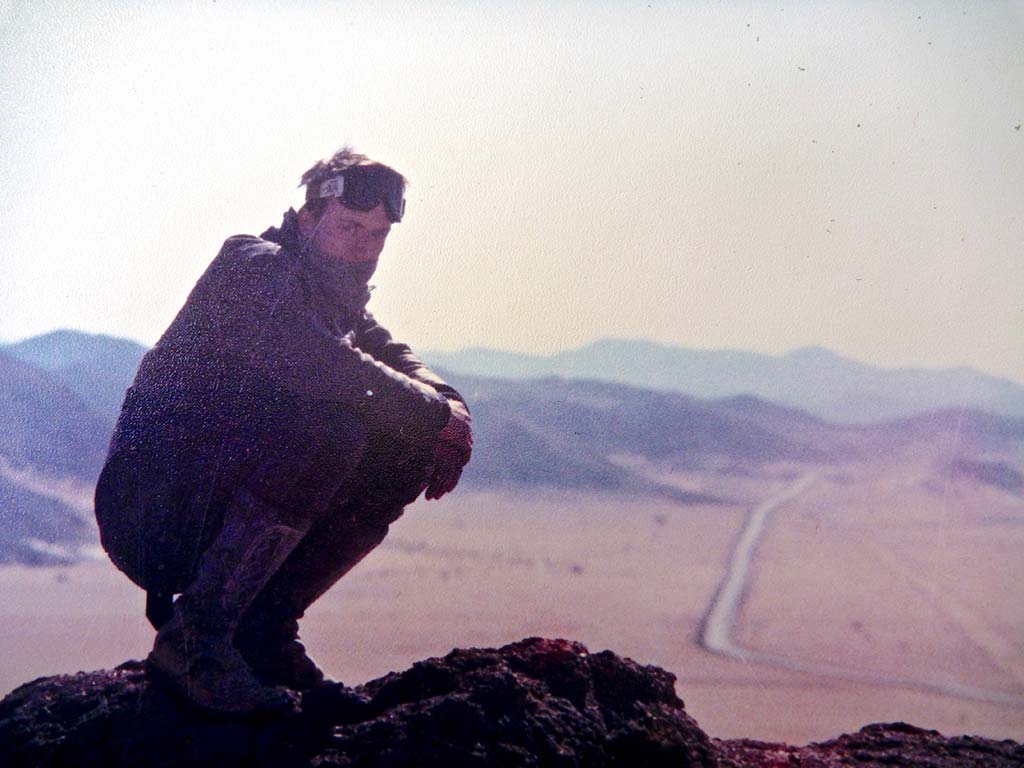

What is it about the Sahara that lures you back time and time again?

I like getting to know one place well and there’s more than enough Sahara to fill a lifetime. I like the weather, geology, pre-history and the space. I get off on the adventure and exploration too, the need for planning and problem solving, plus the navigation and the satisfaction of self-sufficiency.

Travelling is a time machine. A fossil or volcanic extrusion may be millions of years old, a stone hand axe dates from the Palaeolithic, and rock art from 6,000 BC. A desert village may have changed little in centuries and that sand-blasted jerrican is stamped ‘1943’. You can ride through all this one amazing day after another.

You’ve travelled on plenty of motorcycles over the years but is there a particular bike that sticks in your mind as your favourite for overland travel?

I change bikes a lot. It’s where they can get me plus the ease and fun with which they do that counts. Recently I enjoyed the Royal Enfield Himalayan and the Yamaha XSR700, Yamaha, please make a desert sled scrambler of that brilliant CP2 motor. So, on a similar theme, I like the idea of scrambling a Royal Enfield Interceptor. It wouldn’t take much to make that a great travel bike with character and presence but without spending a fortune.

Do you think the world’s experiences with Covid-19, and the resulting temporary loss of freedoms, will encourage more people to pursue their dreams of motorcycle travel in the future?

There will be a rebound but I suspect we’ve just passed peak global travel and tourism. Things won’t get back to how they were. Whether it’s the small risk of catching the virus in a faraway land, the bigger impact of restrictions and regulations or, not least, the economic uncertainty many everywhere are facing, that game is over for the moment.

And on top of the pandemic’s still unfinished impact, current political trends and the coming disruption from changing weather patterns probably means we’re witnessing the end of global motorcycle travel at the scale and ease to which we’ve become accustomed.

I recently spoke to Charley Boorman about his experiences with electric bikes on the Long Way Up. Could we be seeing electric motorcycles popping up in future editions of the Adventure Motorcycling Handbook?

I may give Long Way Up a go if I can pack it into a free trial, though I didn’t get past the fart-lighting episode in Long Way Down. The two have a great rapport but electric bikes were a made-for-TV stunt. Fair enough but can you imagine undertaking such a trip without back-up right now? Of course not.

Until the day we can roll up to a battery recharge bank in Cusco, Khabarovsk, or Kumasi, swap batteries and ride off, electric bikes are going to be restricted to cities or other short-range applications. I was pleased to read recently that the Big Four’s (Honda, Yamaha, Suzuki, and Kawasaki) e-Yan Osaka project to share replaceable battery technology is moving along. ‘That will be cool’ as Charlie might say, but it’s surely a decade away.

If you could give one piece of advice to a budding adventure motorcycle traveller, what would it be?

The more you know the less you need.

What’s next for you? Do you have any travels or new books planned?

My Africa Twin has been stuck in Morocco since the outbreak with a hole in the sump. That needs repair and recovery when the coast is clear. Right now, I’m busy designing and writing a kayak book for a British publisher. I’ve been writing about that for many years, and following a post-lockdown surge of interest in paddle sports, it’s time to make a new kind of hay while the sun does shine.

Find out more about Chris’ travels at www.adventure-motorcycling.com.