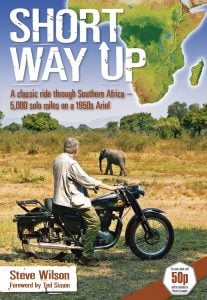

On turning 66, Steve Wilson undertakes one last two-wheeled adventure before resigning to the bus pass: a 5,000-mile round trip from Cape Town to Zambia and back again on a 1950s Ariel. We join our intrepid ABR and his bike ‘Jerry’ at the RSA border…

I had about 175 miles to go to the border with South Africa, which now to me represented an unlikely sanctuary. We slogged south, and the country at first was outstandingly beautiful. On a straight road before the first town of Ngundu, to the right of the highway wonderful tall rock outcrops rose from the red earth. I saw an African in the flatbed of a truck saluting one, and did the same mentally myself. In warm sunlight, pale dry riverbeds and fine forests punctuated the way. Zimbabwe, if nothing else, was beautiful.

But Jerry, as if sensing my desperation to get out of the country, acted up. The engine began losing power and pinking on even mild inclines. My initial reaction was to flog it, “just get me there,” even if Avis had to take over in RSA. Then I saw the folly of that, and began to let the bike find its pace more, and that was better for a while, though it was still pinking at the top of slopes. The probable culprit was the “Blend” fuel, and I could see a lot of debris in the fuel filter, despite having cleaned it out at Karsten’s. I stopped to rest the engine among some particularly lovely wooded hillsides, but soon a young guy came walking past with his girl and began to call out ironically in a falsetto voice, spoiling it.

Underway again, the front end problems re-asserted themselves, not aided by some terrible rain-groove/tramline surfaces. With about 65 miles to go I stopped again to rest the engine and myself, as it was seriously hot now and I was beginning to feel a bit dizzy. We rode on, counting the miles, but things got worse. The country had gone to flat and barren bush, with plenty of cows and some goats ambling across from the unfenced edges of the road. The only features were some fine baobab trees along the way, and plenty of lay-bys, though most were unshaded. The bike was now vibrating badly as well as pinking, and with about 35 miles to go – I couldn’t believe this, we were so close! – it began to slow and falter after the pinking had worsened. I pulled in the clutch and coasted for a while. But as our speed slowly declined, deciding this was not the place to stop I let out the clutch – the engine was still bad – and changed down into third, which inexplicably felt and sounded OK. So we crept onwards in lower gear, counting the miles, willing the bike on.

After eight or nine miles like that I decided cooling off was the wiser course, and pulled into a lay-by on the far side with a sliver of shade from a baobab tree. I trickled forward over the dust till the ground underneath felt firm enough for kick-starting on the stand, then stopped the engine and turned off the petrol. I took off my helmet and jacket, putting them on a concrete table a little way away. I checked the gearbox temperature and oil level, in case something had gone wrong and it was that top gear thing again, but the box was cool and full of lubricant. I poured a little fresh oil into the oil tank. I cleaned out the fuel filter. I changed the plug – the one in there had little silver scratches on the electrodes. All this took about 15 minutes, and it was now around 2pm.

At that point, a white bakkie carrying two Africans pulled in, honking once in greeting. The driver wanted to know if I was in trouble. I began to sketch out the story but he interrupted, “Does the bike run?” I said, “Yes, but not very well.” “Then leave here now,” he said urgently. “It’s not safe, they will take your stuff. Two weeks ago I left one of my truck drivers here, I told him to wait, and by the time I was back from Beitbridge, he had been attacked; he was stabbed.”

I threw up my hands in probably inappropriately mock horror. “Do not stop here,” he said seriously, “or the next lay-by, or the third.” And then he drove off. Feeling like Mole in the Wild Wood, I kitted up, and luckily the Ariel started fairly easily. There was less than 20 miles to go and top gear now felt OK, though the engine was noisy. I passed the other two lay-bys which were as empty as the land around. I felt the urgency. After all the warnings from white friends, it had taken a concerned black to really get to me. I nursed Jerry along, willing him on, past lay-bys with people selling carvings, and finally the first sign for Beitbridge came into view.

I poked and hoped on for a couple of miles, through some rough bits of road, past lorry parks, with all the Ariel’s front end troubles and everything else forgotten in the need to negotiate this last hurdle. There were, of course, no signs, and I had to guess, and ask once, about the way to customs and immigration. I finally pulled up by some parked bicycles in the shade outside a big, busy, likely-looking building. There were too many people hanging around outside filling in forms, so when two kids offered to watch the loaded bike, I accepted.

Then I plunged in, jacketed and carrying the helmet. Inside it was like an old-fashioned bank. I went to a window at the counter, paid $5 for the privilege of leaving, got a gate-pass form, got sent to the immigration window, who were not interested in the carnet but did stamp my passport, paid for the gate-pass and got its first stamp, got sent down the corridor for its second stamp, but there was no one at the window I thought they had indicated, so went back to the first window and got sent to customs, another, smaller adjacent building, for the carnet. Miraculously, after waiting for the guys to finish in front of me, the official there did the carnet business with no problem. Big relief. I thanked him warmly. Back to the original window to pursue the gate-pass, they again sent me down the corridor but this time made it clear that what I needed was not a window but a table in the corner, which I’d thought was money-changing. The lady there scrutinised the Ariel’s log book uncomprehendingly, but stamped the gate-pass – and then sent me back to the first window for a final stamp.

But that was it. Outside, I gave the boys a dollar each, pushed the bike a little way away, put the pass half in the tank bag and stuck the gloves down my jacket. Jerry started fourth or fifth kick, and at the gate before the bridge back over the Limpopo I handed over the pass while keeping the engine going with my left hand, and a young gate guy grinned, “You are an Easy Rider!” It was a plus note to be leaving on. As I moved off, a taxi-bus abruptly pulled in nose first across the lane, but I rode round him and sailed over the river.

Customs on the South African side was predictably more organised. An Afrikaner family I got talking to said that a few weeks before this they had been coming through, and on the Zimbabwean side, when a log- jam had developed in a doorway, an official had come with a stick and started whacking. When one of his little boys started playing up, the man threatened to put the child on the back of my bike. At Customs I got an extravagantly hair-curled, traditionally-built African lady who was flummoxed by the carnet – oh no, the South African problem again! – but she consulted a colleague and soon got it right. Yes! I had cleared the last hurdle on that one.

Outside on the road again I was mildly confused as the N1 dual-carriageway came up quickly, with signs indicating it was a toll road – should I have turned where it had said “Residential Area,” to get to the border town of Musina? But then there was a sign indicating that the town was 10km further on. I nursed the bike along again, pulling left over the yellow line to give way to cars speeding up from behind. The town, when I reached it, rambled, and included an unpaved section of road, but there were some promising-looking eateries, an Avis sign, and even a train station, complete with locomotive. Eventually I booked into the clean but noisy Limpopo Hotel.

At the bar I fell in with a raw-boned, hatchet-faced Afrikans ex-enduro rider who said he had once, racing a 535 KTM, suffered a heart attack in the middle of an event out in the bush. But after an hour, when the support vehicle eventually arrived, he had been conscious enough so that, like a 19th-Century English fox-hunter, he wouldn’t let them cut off his boots, and he had woken up in hospital in just his underpants and his R600 motocross boots. How was it, I thought, that even after the day like the one I had just gone through, other people’s stories always had to gazump mine?

WHO’S RIDING?

Steve Wilson is a leading classic motorcycle journalist and author of the definitive six-volume British Motorcycles Since 1950. He also wrote Triumph Bonneville, in Haynes’s ‘Great Bikes’ series, and his Down The Road, a collection of his best writings about classic motorcycles, became a cult classic. He contributes monthly to Real Classic and Classic Car Mart magazines. He lives in Wantage, Oxfordshire.

THE BIKE

Jerry is a 1958 Ariel 350. Its number plate, dating from 1966 when the frame was re-registered as part of a special, is KYL 938D. ‘KYL’ suggested it had to be called The Killer, though that seemed a bit dark-side. The Killer, however, was ace rocker Jerry Lee Lewis’ tag line, and one ride on this Ariel brought the singer’s immortal lines to mind: ‘You shake my nerves and you rattle my brain’. So I called the bike Jerry. Like my Ariel, Jerry Lee was also a famously awkward and unpredictable character, sometimes lethally so…

THE BOOK

The full story of Steve’s 5,000-mile African adventure on board his 1950s Ariel is available from www.haynes.co.uk, £19.99, published by Haynes. A donation of 50p from every book sale will go to Project Luangwa, a charity organisation established by the Safari Operators of South Luangwa, which helps local communities improve their economy while preserving the environment.

The full story of Steve’s 5,000-mile African adventure on board his 1950s Ariel is available from www.haynes.co.uk, £19.99, published by Haynes. A donation of 50p from every book sale will go to Project Luangwa, a charity organisation established by the Safari Operators of South Luangwa, which helps local communities improve their economy while preserving the environment.