Brendan Layton goes on a safari on two wheels as he rides through Kenya. Watch out for that giraffe!

How did I come to be doing this?’ I thought to myself with a smile on my face. I’m a 45-year old father of two teenagers with a normal job and a relatively normal life and yet there I was, riding through the wilds of Kenya, giraffes to the left of me and hippos to right. It was a bit of a change from my usual trail riding excursions into West Wales.

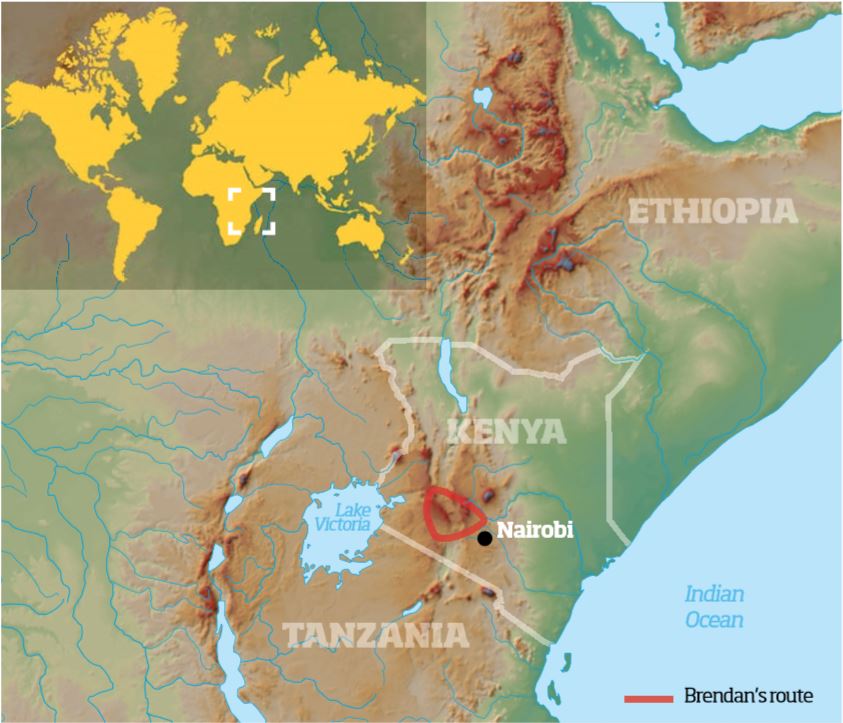

The journey had begun just three days prior when Andy and I had boarded a British Airways flight to Kenyatta Airport. From the tame and somewhat placid surroundings of the UK, we were thrust into the bustling high-rise city of Nairobi before being whisked away by Iain, our guide-to be, to the small industrial town of Thika, just 25 miles northeast of the capital. It was from here that we were kitted out with bikes, we had the choice of either a Suzuki DRZ400 or a Honda XR250, and sent on our way into the plains of Kenya, following Iain like a row of ducklings.

It wasn’t long before it dawned on me that I actually hadn’t ridden a bike in quite a few months! Fortunately, while I felt uncomfortable in my surroundings, I soon noticed that the bike I was riding (I’d opted for the DRZ) was relatively similar to the one I had at home, and I began to get the feel for it almost instantly. It was a sensible choice of bike, not too heavy and more than capable on the off-road sections of our ride, and there were to be many. As we left Iain’s colonial cottage we turned onto a sandy path and a heron flew off in front of us. It was the perfect introduction to what would be eight days of riding through Kenya’s beautiful and wild landscape, with mostly nothing but our own thoughts, two wheels and the occasional giraffe, zebra or hippo joining the group.

The roads were typically dusty and very few were tarmacked but the riding started off easy. Down almost every road we passed countless waving locals, adults and children alike, stopping to stare at the strange, heavily clad aliens go by. It was at this point, after getting the hang of the bike for a few miles, that my nerves began to subside, excitement overwhelmed me along with the realisation that we were there, in Kenya, doing it! I glanced at Andy and shouted “we’re here! We are riding in Africa!” and a childish grin planted itself on my face.

The riding only got better as we climbed gently through farmland. Bright, colourful crops, people and endless blue skies were bombarding us with a feeling of joy. We passed several small motorcycles going the opposite direction carrying five foot wide loads of farm produce, animals and more. We carried on up until we reached the top of the road and spread out before us was the first of many incredible views. Stretching out for miles was the valley below, tiered in many different levels for the coffee farmers.

I’d often had thoughts of riding in Africa and having the feeling of being watched. In my imagination, I was being stalked by a lion or some other big cat, but on top of this hill, we had the first realisation that in Africa you are never truly alone. From out of nowhere two locals came over and started chatting with us. We weren’t on a ‘usual’ tourist route so they were surprised to meet the group. It dawned on us that we had stopped at an entrance to a school and two small children appeared, followed by almost a hundred more! After lots of smiling, staring, waves and cheers we drove off down the lane feeling like undeserving celebrities.

We had spent most of our evenings camping at sites selected by Iain, it was a strange mix of luxury and basic overnighting; DK, the driver of our 4×4 support vehicle, would head off in advance of us and set up camp, pitching all the tents and Will, our Kenyan guide, would go about getting dinner on. Camp showers were open-air with a suspended bucket and a tap. Perfectly adequate and kind of fun, but they were a cool, sharp introduction to camping in Africa.

The sun became our daily alarm clock and it appeared and disappeared as if someone was flicking a light switch, rising at 6 AM and setting at 6 PM.

Most nights I slept like a baby, the noises of the animals surrounding our camp acting as a lullaby. Though to others, particularly Derek and Neil, two brothers from Wales, it meant staying awake the whole night worrying about what that noise was!

We set off that morning into the wild, the land becoming more open as we rode and I thought about the term ‘big skies’ which I had so often read in travel books, I now knew what they meant. Zebras, giraffes and gazelles all grazed to the side of our trail and we made our way through rutted forestry tracks. We had all been so engrossed in the riding that it took Iain to point out the massive mountain dominating the horizon; we had been riding in Mount Kenya’s shadow all day and we didn’t even realise.

The ride went on, over the tourist trap that is the equator crossing (which was also the home of countless street sellers) and past a Kenyan military base until the tarmac stopped with a definite line in the road.

At this meeting of terrains, Iain warned us that we wouldn’t see the tarmac again for 200km.

The landscape immediately changed into red, dusty soil and typical African bushland. To mark the occasion a tower (yes, the collective term for giraffes is a tower) of giraffes ran alongside of us and zebra and gazelle grazed a little further on. We had begun our safari on motorcycles. The road continually curved climbed and fell across the plains, the surface constantly changing from sand ruts to gravel to keep our concentration keen. The Land Cruiser had gone ahead to scout out animals and after a few miles, we saw him reversing towards us gesturing for us to stop. Around the corner was a herd of elephants. We parked the bikes up and climbed on to the roof rack of the 4×4, Will took us to within a few feet of the massive animals and we sat for a while taking photos and observing their magnificence.

They eventually wandered off so we rode on – more giraffes, zebras, gazelles and now dik-diks (a type of small antelope) were ever-present. We came to a makeshift roadblock; felled trees across the road, which had been created to warn that the bridge ahead was down. Two big Volvo diggers sat in the river below and the British Army were stood on the other bank on what looked to be a newly constructed bridge base. They explained that we couldn’t get across at this point so we would have to take a 60km detour into town or follow the river south to the next bridge. The only issue with that plan was the bridge belonged to a farmer and he might not let us cross, it sounded a lot like Monty Python’s Bridge of Death.

As it turns out, the detour to the farm was totally worth it. The farmer was happy to let us cross and after a few miles, the land rose steadily until it felt like we were crossing the top of the world. All around us as far as the eye could see the earth curved away from us. Eventually, Lake Baringo came into view far, far below. The road wound around the mountainside to follow the line of the water, all the way to the other side of the huge 50 square mile lake, to our camp for the night, Robinson’s camp.

We were somewhat surprised to find the campsite flooded and full of overland trucks with tents pitched wherever there was a break in the water.

Our tents had been erected in a small circle at the edge of the site so we ditched our gear and had a meal in the sand-bag-surrounded café. Just on the other side of the bags we could see and hear hippos, crocodiles and numerous birds.

We spent the next day exploring the area around Robinson’s camp, taking a narrow boat to an island on the lake where African fish eagles liked to hang out. Our captain threw a few fish into the lake, a few feet away from the boat, and one of the eagles swooped down to collect it. We really were being spoilt for wildlife on this trip.

After an eventful day, we spent the night in the same place. As I walked back to my tent to get some sleep Will stepped out from the darkness and stopped me. He shone his torch into the black that enthralled our surroundings and just a few feet away a hippo’s eyes lit up. He warned me to wait until they were further away before I carried on. Hippos are one of the biggest killers of humans from the animal kingdom in Kenya and with that in mind I took Will’s advice. A few moments passed and I was finally able to return to my tent. Just as I was dozing off I heard a sound from outside. The hippo had returned. Amazingly, just two feet away from my head, it began to graze, making distinctive chomping noises as it ate. I stayed very still. With just the thin, lightweight wall of the tent keeping me safe there was little I could do but hope that it didn’t sit on me!

The next thing I knew, the daylight switch had been flicked and the hippos had disappeared.

The morning after the close encounter we said goodbye to Lake Baringo and headed to Lake Bogoria National Park. Due to another bridge that had collapsed our group decided to split up, with Iain, Andy and I taking the longer, trickier route through Lake Bagoria. And I literally mean through Lake Bagoria. As we approached the national park it became apparent that Bogoria was also flooded! The road ran straight into the lake, but a very rough trail had been cut in place above the waterline. We followed this with the midday sun beating down on our helmets, only first and second gear would do as the riding became tricky.

After a while, the trail eventually ran into the lake as well. As I sat there thinking that we’d have to turn around and find an alternative route Iain rolled forward and set off into the water. There was no exit from the submerged road anywhere in sight so I sat and watched nervously as Iain journeyed further out before turning behind a line of trees. Occasionally I caught a glimpse of his bright white helmet through the foliage and it came to a standstill about 300 yards away.

I was beginning to wonder if he had gotten stuck when I heard a shout. We didn’t know if he was calling for us to follow or because he needed help; either way, Andy and I rolled our bikes into the water. As we rode onwards I became aware of the possible inhabitants of this soda lake, and nerves started to kick in when I realised that I could no longer see the bottom. Nevertheless, we trudged on and, as it turned out, Iain had made it to the other side safely.

The going got easier but the temperatures increased and our bikes began to overheat so we took a break at the closest shelter we could find, a small gatehouse. Everything was getting too hot in the 40C sun, the shock absorbers were hot enough to burn your hand, radiators were boiling over and the oil temperature light glowed brightly on one bike.

We started downing our water to rehydrate only to realise that we had just four litres left between us and the bikes. To make matters worse there was still 75km to go before we reached the others and the next source of water.

We asked the gatekeeper if he had any more H2O, to which he told us that he didn’t, but he did have an immaculate DT175. After discussing the road ahead we were reassured that it would be better than what we had experienced already today and that we would make the 75km before nightfall. As we set off I managed to stall the bike, put my foot down and slip. In an instant I felt agony in my hamstring, I think it was torn. After a few miles, I was unable to stand on my injured leg and was dreading the rough riding as I fought just to sit on the bike. Further on down the road, a lorry was stuck in the river bed so we skirted around, crossed the equator (south to north this time) and made our way to Kembu Camp, 2,209m above sea level.

Kembu camp could have been in Derbyshire or the Cotswolds due to the lush, rolling green landscape. We were relieved to find that our tents had already been erected and the rest of the team had been there for some time. We got some beers in and the temperatures dropped to 11C over the course of the evening.

The remainder of the trip saw us riding back towards Iain’s cottage, past Menengai volcano, the second-largest volcanic crater in Africa, and along a perfectly flat, smooth tarmac road that had been built by the Chinese for Kenya’s oil industry. We followed the Great Rift Valley before dropping into its heart where the scenery changed massively. From the green hills before we were now riding in sand and dust, with the vehicles in front spewing up massive dust clouds that prevented us from seeing oncoming traffic. It was an experience but hardly a fun one.

As we approached Lake Naivasha the road improved and the population rose. The end of the trip was approaching; the remote feeling was slipping away. We took the opportunity to have a rest day at the lake so we rode to Crater Lodge. For the most part, we sat there, overlooking the lake, the tranquillity, lack of stress subduing us, with nowhere to be and nowhere else we would want to be it was a magical moment and the perfect way to end the trip. Far too soon after this, we were back at Iain’s base, eating cake and honey before going to the airport to fly home.

So many clichés spring to mind when I think about the ride. Life-changing is the biggest one though. It was over too soon, but I know that Africa won’t be the end of my adventures.

Who’s riding?

Brendan Layton:

Brendan, a father of two, was born and bred in Chesterfield. For the last nine years, he’s been a self-employed trader of motorcycle accessories so he gets to travel the country and visit shows on most weekends. He’s always had a keen interest in travel, having been to many parts of the northern hemisphere, both for work and pleasure. Only recently has his love for motorcycles and travel come together after meeting various overland motorcycle travel authors and reading their books.

Andy Stickly:

Father of three now grown-up children, Andy has worked in the motorcycle industry for over thirty years. He’s a partner in a Kidderminster based motorcycle shop, which specialises in classic bike parts. He also travels to sell his goods at bike shows around the country. Andy has trail ridden in Wales for many years mainly on Japanese dirt bikes.

The bike: Suzuki DR-Z400

The bikes were very well suited to trail riding in Kenya. The standard seat height (890mm) suited us, but the rest of the bikes had been lowered for the other riders. At 139 kg they are not heavy bikes so the forest stages were not a problem and they are not so small that distances became an issue either. The standard 10-litre tank meant I was glad of the support vehicle, as off-road this equated to less than 80 miles range. 35 – 39 bhp is enough for the Kenyan roads, occasionally hitting 60 to 70-plus mph on was very exciting, but probably foolish. The few tarmac sections showed the DRZ’s main weakness, the MX style seat soon becomes uncomfortable!

Beware the Matatus

While most of our riding was off-road we occasionally had a few encounters with traffic. Iain had warned us about ‘matatus’ and it wasn’t until I saw them first hand that I realised why. They’re small minibuses designed to carry about eight people, but in Kenya, it’s not unknown for them to carry double this amount. Some of them have doors open with people’s rears sticking out and the drivers are often high to help them stay awake! And they don’t take it easy. On heavily potholed roads the other road users would drive with caution, the matatus however would overtake and undertake everybody and everything at any time, and then swerve into the side, brakes on full, to pick someone else up. I’m sure I don’t need to say it, but keep your wits about you when you spot a matatu!

Staying hydrated in Africa

It wasn’t until partway through the second day that we realised how serious an issue dehydration can be. It’s surprising how much fluid you can lose in sweat while biking over difficult terrain and if your mind is on the riding then you often forget to rehydrate. We always made sure we had some water with us so that we didn’t run out – a hydration pack on your back would be a great addition to your kit so you can drink on the move.

Want to do What Brendan did?

Here’s how you can…

How long to take off work?

I rode with Iain from www.SafariRiders.co.uk on a trip organised by them using their bikes and support. This basic trip is seven days riding and nine nights, which can be done in just over a week off work, arrive Saturday fly home Monday. We extended our trip to suit the cheapest flight options around when we wanted to go. The saving on flights paid for the extra days in Kenya and gave us the benefit of nine days on the trail allowing more time to mix with locals and at points of interest along the way. If I was to do a similar trip I would extend it still further as it was all over so quickly!

How do I get there?

Air freighting your own bike is possible to Kenya but bureaucracy and bribes are tough hurdles to overcome especially for the Europeans who are assumed to be rich! It is possible to fly from most major airports in the UK, by changing in Istanbul or other places for the cheapest options, starting at around £380, if timed right. We chose to fly direct which is more limiting. Only three operators seem to do direct flights from the options I saw. We chose British Airways, which is not the cheapest (£620 in our case) but had a very generous luggage allowance, allowing two big kit bags each which fitted our gear in easily.

Which guided motorcycle tour operators serve Kenya?

There seem to be a few organised trips that start in Nairobi heading to South Africa, including one with Charley Boorman, but the costs are on a whole different level to those of this trip staying within Kenya. Starting at £1,280 pounds plus the flights and meals, this Safari Riders option was the most affordable. Iain is English, and thus there was no language problems for us.

When should I go?

Kenya is on the equator, hence the weather does not vary greatly, for most of the year. In the spring April/May time, there is a rainy season (the big rains) and the beginning of September can also be wet (the small rains). I would avoid both of those times as though still warm, things quickly get very muddy.

What do I need to pack?

Some kit can be borrowed from Iain but I took all my own, for comfort. Hot days require a well-ventilated kit.

- I took my boots with a pair of long thin cotton socks to wear each day.

- Helmet with vents. Most of the group wore MX style helmets, but it is very dusty so I was pleased to be wearing an adventure style with a visor and sunscreen built-in. The visor minimised dusty faces.

- MX style jeans and knee protectors.

- Body armour.

- I had thin MX style gloves, which offer some protection without being to hot.

- I also had an aqua pack rucksack which is useful for topping up on fluids and keeping a good camera in.

- Thin sleeping bag and a travel pillow.

Riding difficulty?

90% of the trip is easy dirt trails, with big potholes and sand patches to be wary of. The short forest section added mud and wet grass which jumped the difficulty up a few notches for a short while. The road to Naivasha was long and sandy in varying depths. This created some difficulties with front wheels washing out for a couple of our companions. Will my standard insurance cover me for riding off-road in Kenya? I had European holiday insurance free with my bank’s current account, this covered me for an organised guided tour in Europe and for £40 was upgraded to cover Africa too. Kenyan Law requires each vehicle to be insured not the rider, hence the bikes were already covered by Safari Riders.

Vaccination and inoculations?

Professional medical advice should definitely be sought well in advance of travelling to central Africa. Kenya requires some inoculations for hepatitis, typhoid and diphtheria. Some surrounding countries require yellow fever certification too. The UK medical profession strongly recommends Malaria tablets to be taken for most of this region, though 80+ percent of our tour was above 6,000 feet where Malaria isn’t present. Local advice differs from that given in the UK. Hence it is necessary to seek professional advice. Central Kenya seemed to be a relaxed un-touristy and safe place, but several of the borders of Kenya and central Nairobi have British travel advice warnings. We picked a guided trip that didn’t infringe on any of these areas.

Photos: Brendan Layton