Janelle Kaz battles the Trampoline of Death as she undertakes her mission to document illegal wildlife trafficking in Colombia

In Colombia, if you don’t like the climate or the landscape, just keep riding; it is bound to change drastically, and very quickly. Colombia has the most diverse landscape of any nation on this planet. This lends itself to the diversity of its flora and fauna, not to mention the amount of gear you’ll need to take with you on your motorcycle adventure there.

Packing for this journey was not easy. My mission was to document the positive actions being taken to protect ecosystems and combat the illegal wildlife trade, and that meant that I’d be travelling to many different types of environments in which rare and threatened species exist.

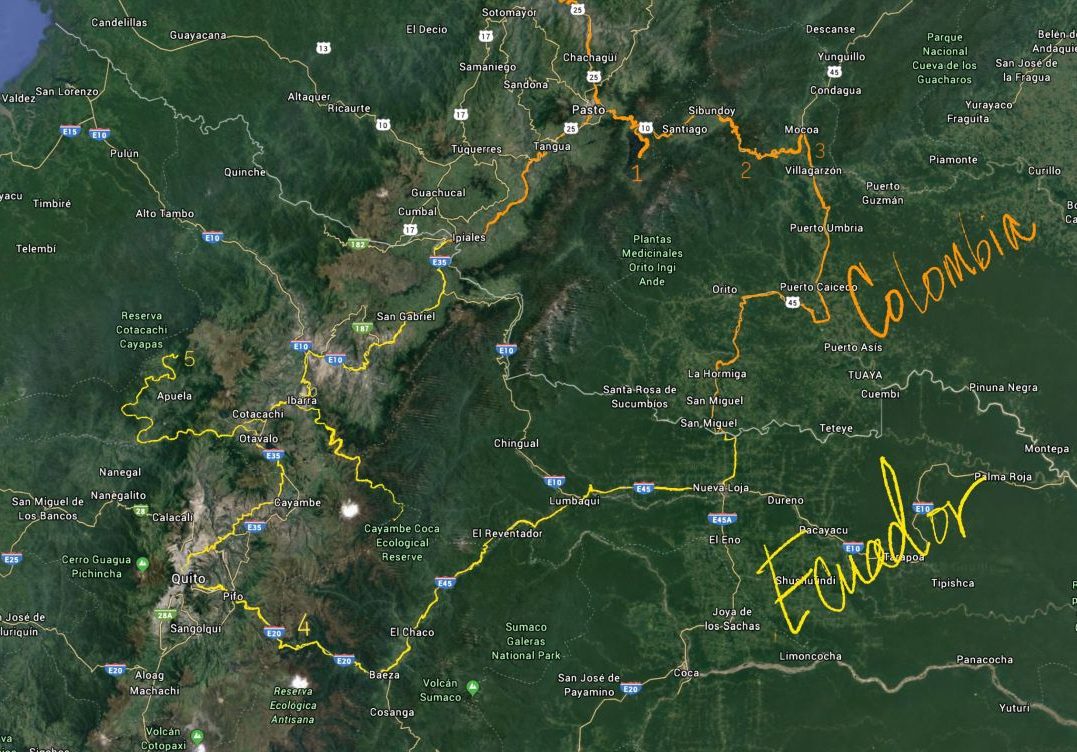

This contrast in landscapes and climate is certainly true of el Trampolin de la Muerte, ‘the Trampoline of Death’, a stretch of dirt and gravel that connects the city of chilly, mountainous Pasto to humid, hot Mocoa in the south of Colombia.

This is the narrowest stretch of the Andes, traversing the unique Paramo ecosystem down into the Amazonian jungles. It’s hard to resist riding a road with a name and a reputation such as this.

Pasto is the largest city in the south of Colombia before the border to Ecuador. Heading east from there, the road starts out with smooth pavement, winding you towards Laguna de la Cocha. This lagoon should not be missed and is a short detour from the main road.

It is a beautiful, mist-covered lake with slipper-like speedboats, chilly fog draped across its quaint canals, and salmon-coloured trout cooked many different ways, each one of them delicious. Laguna de la Cocha is a natural wetland reservoir of biological, cultural, and international importance.

La Cocha is one of the largest and best-preserved lagoons in the northern Andes, and it can be found on the eastern slope of the mountains of Nudo de los Pastos, at an elevation of 2,760m. There is an incredible awareness of the medicinal and spiritual quality of the plants in this area, and the indigenous people, bundled in scarves and knit ponchos, know that this area is worth protecting and the knowledge preserving.

In regard to the indigenous communities who conserve the local ecosystem, you’ll be respectfully ripping your bike through, you can learn about the medicinal and shamanistic value of plants at Alquimia, a school of Amazonian Alchemy.

It was at this school that I learned about a reserve run by a native family working to protect the balance of the Laguna de la Cocha at Reserva del Buho, with accommodations and excellent food.

From there, the road ascends into the paramo, a high-altitude ecosystem that is home to the spectacled bear, the only South American bear. At this altitude, the temperature gauge on my bike read 17C, but I suspect the temperatures, with wind chill and blanketed fog, were actually much lower.

The road becomes dirt and narrows after Sibundoy, a great place to stop for lunch and a legendary town for ethnobotanists with the highest concentration of psychoactive plants in the world.

I’ve heard there are blue-bird days along the Trampolin a few times a year, with views of jungle landscapes, rolling seas of lush green down the 1,000m sheer drops into the valleys below. This was not the case as I travelled, embraced by perpetual clouds and moving mist the whole way.

Occasionally though, the mist would clear, making evident the fast pace at which it moved and revealing how the road was carved into the sides of the steep green mountains, showing the height and the precarious placement of this path less travelled.

For obvious reasons, this route is not advised in severe weather conditions. The surface of the road itself can get very slippery and the steep slopes are prone to landslides. Storms often leave it impassable, even with a 4×4 vehicle.

Hundreds of people have lost their lives along this narrow stretch of road since it was built to transport soldiers in the 1930s. With the mist looming heavy, I lost count of the number of river crossings I forded, as waterfalls cascaded right down across the road, indifferent to its presence.

Often you are crossing the same river multiple times as you snake up and down the more than 100 switchbacks and hairpin turns of these steep mountains. Depending on the amount of recent rainfall, some of the crossings can be quite deep, with large stones which are difficult to see in the river bed. Take caution.

Guard rails have been put up in sections of the road, but there are still many stretches without them where there isn’t room for more than one vehicle at a time and the trucks will not wait for you to get out of the way.

When you finally begin the final descent, you’ll soon see banana trees exploding out of the landscape, colourful houses, and the air temperature can easily climb more than 15C from that of the paramo. At this point, you’ve just crossed from the cool, dryer mountains of Nariño into the wet, sticky jungles of Putumayo.

There are many notable waterfalls south of Mocoa, Fin del Mundo (End of the World) being the most famous of them all. I had a date with the protected forests of Los Cedros in Ecuador, which are being encroached upon by miners, so from the End of the World, I travelled south to cross the border.

I crossed into Ecuador just south of La Hormiga. The Colombian military guard at the bridge wanted to add me on Facebook before allowing me to cross the river into Ecuador. I rode across, seeing all the welcome signs, but with no office in sight to receive passport stamps.

It felt way too easy. I turned around just in case I missed something. I saw a guard lounging under an umbrella at the bridge and he told me it was a couple of miles ahead.

Once I arrived, I saw hundreds of Venezuelan refugees, their luggage, and their makeshift camps strewn around the perimeter of the building. There was a crowd around the entrance to the main door and it seemed like the people were upset as a guard declined entry.

There were sick children at a medic table crying. An officer walked me through a crowd to let me in the doors, where there was zero indication of what to do next. After getting my stamp out of Colombia from the one and only woman working there (who did not seem happy), I then got in line for the Ecuadorian side and essentially stood in the same spot for the next two and a half hours.

There was one woman doing all of the processing for anyone who wanted to get in and out of Ecuador and she would occasionally just leave her desk, stepping into a back room, not returning for quite some time. There was no air conditioning and my arms were full of my riding gear and documents. The line stood still. A woman outside lost consciousness and her limp body was carried into the building.

For as long as this process took me, I still felt an incredible, almost palpable feeling of my own privilege. I had an American passport, all I needed was a stamp and I would be on my way. Who knows how long they would stay at the border and what lies ahead for them.

What was it that they were forced to leave behind? I’ve heard that the economy is so bad in Venezuela right now that they are selling food by the spoon. My heart goes out to them, but such sympathy is insignificant to their challenges.

The disparity between us humans is tremendous. How awful that people can live so lavishly, so in excess, when others are so desperate and in need; that the dogs of the rich eat better than the children of the poor. I hate it.

I rolled into the nearest town, Lago Agrio, just as the sun was setting, parked my bike and settled on the first hotel I looked at, after he offered a better room with my own bathroom and a window for the same price. Ecuador takes American dollars, which is quite a strange quality and makes the country slightly more expensive.

The next day I set out for Quito. I ascended into the cold. I stopped for a simple meal of eggs, rice, and avocado. It was at this meal that I learned that Ecuadorians drink dehydrated instant Colombian coffee. I declined and just drank the hot water instead.

From there, wet and cold, I pressed on, passing some huge waterfalls and arrived in the paramo. At this point on my journey I had crossed the Andes a few times already, and completely underestimated the pass between Baeza and Quito.

I had to stand up on my pegs for much of the journey just to keep warm, to keep blood flowing to my limbs. The moisture swirling about the road was totally surreal; the word ‘sublimation’ just kept rolling through my mind.

It was like a road of dry ice, and it just kept climbing higher. When I stopped to take a video of this otherworldly view, my motorcycle immediately died. Being carburetted, it was running extremely rough, almost not at all in the thin air. I had to stay above 5,000rpms just to keep the bike alive, which meant second gear most of the way.

I couldn’t tell if the sides of the road were covered in frost and it was sublimating, skipping the liquid phase altogether, or if it was mist gathering on the edges of leaves and swirling above. I couldn’t stop to find out. My fingers and toes were completely numb and yet the road just kept climbing.

I saw many signs for spectacled bear crossing (Tremarctos ornatus, ‘oso anteojos’ the only bear of South America, which I’ve named my bike after) and sent all of my motivating hope from wishing for the road to stop inclining to that of spotting one of these incredible animals.

The road then reached a point where there was zero visibility, just a wall of white with occasional swirling. I knew I had to keep going, to move through this place as fast as I could, which unfortunately was somewhat slowly, in second gear at 5,500rpms.

Finally, a break in the white. The top ridgeline, with dry rolling mountains on the other side, sun hitting their golden grasses – a drastically different ecosystem and even with a glimpse of blue sky. I made it.

The temperature began to rapidly increase during my descent, and with it, the feeling back into my extremities. With my day beginning in Lago Agrio at an elevation of 297m and the road reaching 4,060m, a climb of 3,763m is nothing to turn your nose at.

The descent into Quito felt glorious and entering into city traffic from that mountain top scenario completely bizarre. The following day I got trapped in a sauna (after I had cranked it upto 70C while still trying to warm up from the mountain pass), perhaps one of my worst nightmares.

The doorknob was broken, the inner metal components completely missing, and they were grinding metal outside so no one could hear me scream. Obviously, and thankfully, I escaped.

It seems comical to travel solo by motorcycle in such harsh conditions and then almost meet your demise from something designed to help you relax. If this isn’t an indication to go out and live your most daring life I don’t know what is.

The Bike

I’ve been riding for nearly 15 years and am presently exploring Colombia and Ecuador on a Royal Enfield Himalayan. The bike has been great so far, incredibly reliable and enjoyable to ride on and off-road. The mechanics of the bike are straightforward, and I have had zero problems with it on the 5,000 miles I’ve tallied up so far.

The bike is a bit heavy for its engine capacity and the breaks could be a bit better, but other than that I’m tremendously pleased. You can’t beat the look, the reliability, and the fun of this bike for the price.