Throughout history there have been various influencers in the world of motorcycling. Carl Stearns Clancy proved that long-distance adventures were possible when he rode around the world in 1913, and, like them or loath them, Ewan and Charley undoubtedly popularised the adventure bike movement with their Long Way Round series.

While these figures from history have had something of an impact on our riding lives, there’s one character who’s legacy affects us every time we sit in the saddle. That man is Lawrence of Arabia.

Lawrence of Arabia, or TE Lawrence to give him his ‘proper’ name, was a British archaeologist, military officer and diplomat who was responsible for mobilising the Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire.

His extensive cooperation with the Arab people led to him becoming a highly respected adviser to their cause, and he led small forces against the Turks throughout World War I, attacking communication and supply routes.

While accounts of his exploits were largely sensationalised by eager journalists, they led to him acquiring worldwide fame. Throughout his life he nurtured a love of motorcycles, writing of the “lustfulness of moving swiftly” and the “pleasure of speeding on the road”.

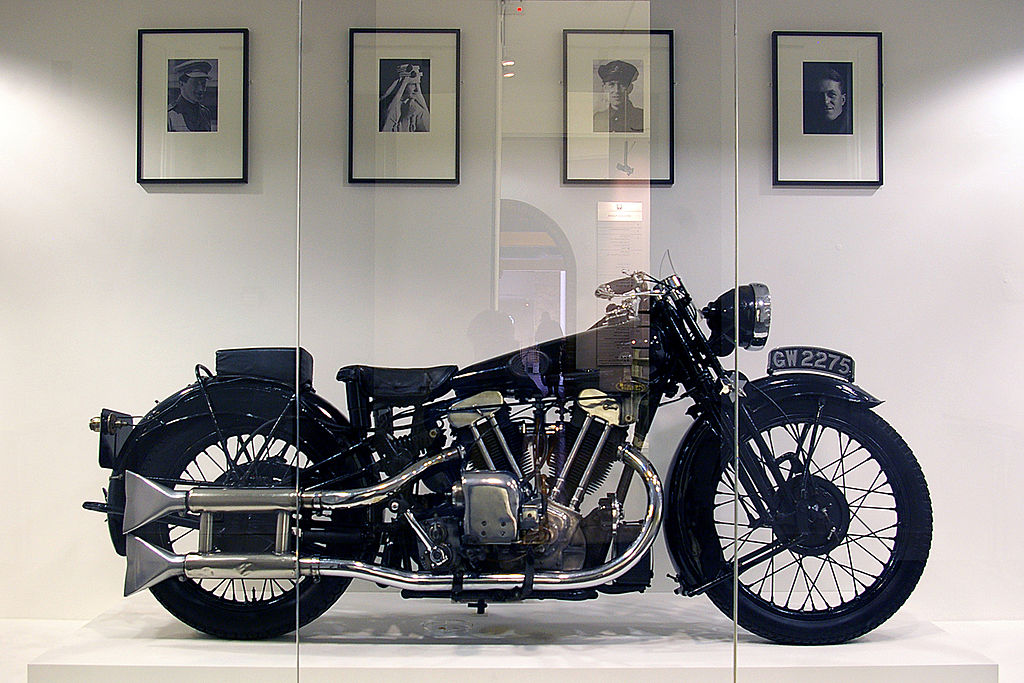

This affair with two-wheeled speed led to him owning eight Brough Superior motorcycles, his last ride being on a Brough Superior SS100 which had been guaranteed to reach speeds in excess of 100mph.

On May 13, 1935, while out for a ride near his home in Dorset, Lawrence came off his bike as he tried to avoid two kids on their bicycles. Six days after crashing he succumbed to his injuries.

When Lawrence died in 1935, he unintentionally set in motion the move to make the wearing of motorcycle helmets compulsory for all riders.

The Brough Superior SS100 on which Lawrence crashed

A post-mortem was performed on Lawrence’s body by Hugh Cairns, one of Britain’s first neurosurgeons, and it was established that he had suffered “severe lacerations and damage to the brain” during the accident, presumably from trauma.

Such was the extent of these injuries that it was noted that if he hadn’t succumbed to them, he would have most likely been left blind and unable to speak.

As a result of this finding, Cairns began to study evidence of head injuries suffered by bikers. It took six years, but in October 1941 he published his findings in the British Medical Journal, in a paper titled ‘Head Injuries in Motor-cyclists – the importance of the crash helmet’.

Hugh Cairns

His paper concluded that of the 1,884 bikers who had been killed on British roads in the 21 months leading up to WWII, two-thirds had suffered from head injuries.

While Cairns didn’t claim that helmets would save every rider, he was keen to point out that they would help with rider safety in a number of occasions. “There can be little doubt that many patients in this series would have lived if their heads had been adequately protected,” he wrote.

Such was the extent of riders not wearing helmets, Cairns was only able to find seven crash victims who had been wearing head protection at the time of their accidents. All seven had survived. “In all of them the head injury was mild, though in four there had been considerable damage to the crash helmet.”

On the back of Cairns’s findings, the Army, which had been losing two riders a week in motorcycle accidents, ordered all dispatch riders to wear helmets. This was in the 1941, and by 1946 Cairns published a study that showed more compelling evidence of the benefits of wearing a crash helmet.

Total motorcycle deaths had fallen from almost 200 before the Army introduced compulsory helmets, to just 50 at the end of the war.

British military riders with their helmets

Despite the findings and conclusive evidence the idea of making it compulsory to wear a crash helmet drew criticism from those who defended individual freedom and the right to choose.

One such opponent being Enoch Powell who said: “The maintenance of the principles of individual freedom and responsibility is more important than the avoidance of the loss of lives through the personal decision of individuals.”

Despite Powell’s opposition, in 1973, 48 years after TE Lawrence had died and Cairns began his study, the House of Commons voted to make wearing a crash helmet compulsory for motorcyclists. Unfortunately, Cairns was not around to witness the passing of the law as he died in 1952.

It might have taken nearly half a century, but together Cairns and TE Lawrence had brought about a law that has no doubt saved many lives throughout the UK.