Simon Thomas and his wife Lisa immerse themselves in 3,000 years of history as they follow the ancient Silk Route along the infamous Pamir Highway.

Since time immemorial, the Silk Route in Central Asia has existed as an artery of trade connecting west to east, and north to south. Contrary to its name, the Silk Route is not a singular road but a web of ancient tracks and rock-strewn trails trodden for millennia by travellers, merchants, explorers, soldiers, and kings. Over 3,000 years of meandering history is carved into one of the most striking landscapes in the world. Our dream of riding the Silk Route is now a reality, and we must ride it successfully if we are to reach Iran and continue our westward journey.

We wake in Kochkor-Ata, a small village northwest of Jalal-Abad in Kyrgyzstan. We’re sitting cross-legged around a tattered Persian rug joined by 10 or so construction workers, each covered in paint, mud, and sawdust, watching us intently as we munch on mouthfuls of stale bread and pieces of fruit. The smell of concrete hangs in the air. We pay our bill for last night’s accommodation in their locked compound by handing over two pirated DVDs we’d picked up in central Russia. It’s great when you realise that money isn’t the only currency when you travel.

The Siberian town of Novosibirsk, where we collected our Kazakh visas three weeks earlier, is but a fuzzy memory. We now only remember Kazakhstan as a blur, with fragile recollections of paperwork, more visa applications, and nights spent in old mental asylums now posing as soiled motels. It’s midday as we ride southeast around the low-lying Fergana Mountains before turning southwest and entering the ancient Kyrgyz city of Osh. Market stalls spill their wares into the streets, selling all manner of items from torches to goat heads. A few domed mosques dot the city skyline making the scene feel familiar, almost Moroccan. Hidden from view inside a small café, we devour a bowl of rice flavoured with the ubiquitous mutton fat. As we eat, locals stop, stare, and finally crack huge smiles as they walk past the parked bikes.

The teeth of the Pamirs

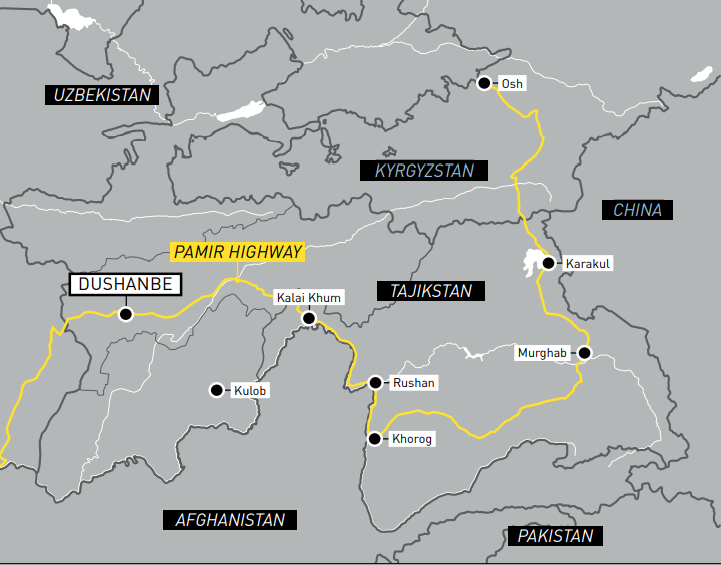

Back on the bikes after lunch, Lisa’s BMW F 650 GS thumps a steady rhythm as we pick up speed on serpentine tar that stretches out below us. The Pamir Highway (M41) disappears from view and reappears as it snakes its way between layers of orange and caramel mountainsides. In the distance, the teeth of the Pamir Mountains rake the sky. My GPS lists our destination as Sary-Tash, a small village on the Kazakh-Tajik border, and we need to press on if we are to cross the Taldyk mountain pass before nightfall.

With investment from China, the length of the lower M41 is being torn up and replaced. It’ll be a delight in a year but right now it’s a nightmare. Standing up on the pegs for better control over the mixture of tumbling large rocks and loose soil, we round a wide bend, our progress brought to a sudden halt as a half-hearted flag bearer waives us to a stop. The scene down in the lower valley through which we are about to cross looks decidedly post-apocalyptic.

Dozens of eight-wheeled, rolling metal giants belch diesel fumes into the sky as they claw and tear at the mountainsides. We choke on the thick clouds of dust these monsters produce as we become stuck behind two of them as they rumble through a long, narrow gorge. With a deep breath and fingers crossed, we plunge into the airborne debris and emerge safely on the other side. We are instantly transported back to northern Argentina, the landscape painted in shades of yellow and tangerine red, the tall peaks of the Alay Mountains in the distance brought out in sharp relief by the royal blue sky.

Perched atop the Taldyk Pass at 12,000ft, we gulp down the thin air and watch the panorama bathed in a translucent mauve. Night is coming fast. Looking out across the Alay Valley, we watch the lights of a distant village twinkle to life as small generators kick into nightly action. The temperature has plummeted to -9C, and the snow-fringed track and slippery switchbacks tug on our already frayed concentration as we work our way down the backside of the pass toward the sanctuary of the village below.

On an unlit path in Sary-Tash, I suddenly barrel into a deep water crossing and barely stay upright before pulling up outside a small homestay where we peel our stiff bodies from the frozen bikes. Exhausted and wet, we settle down in a whitewashed room lit by a single candle. We can barely move inside our sleeping bags under the weight of half a dozen old rugs for warmth and soon fall into an exhausted sleep.

The next day, wearing as many layers as we can find, we head for the Tajikistan border. We ride the short two-mile track to the base of the Alay mountain range, the route ahead indistinguishable among the vast slabs of rock and thick, snow-covered ground. Inside the small border compound, we complete the exit paperwork and steel ourselves against the plummeting temperature outside. Soon the patchy tarmac turns to red clay as we climb in altitude in second and third gear. We’d read countless stories of the severe weather in this region, even in summer, and here we are with winter closing in around us, literally. We are giving this range the full respect it’s due. Two tired Brits without cell or satellite phones could easily get in trouble up here but it’s impossible not to feel the thrill of adventure.

Kalashnikovs and toenails

We crest a rise and the Tajikistan border compound comes into sight. Two large rusting fuel tankers rest in the red mire and are now in active duty as the passport offices. Half a dozen young (and presumably bored) soldiers, Kalashnikovs slung over their shoulders, saunter outside. Inside the cramped room the scene is bizarre. By some miracle, a set of bunk beds is squeezed in, occupied by a guard who sets about our paperwork while only wearing his stained thermals.

The longest set of yellow toenails I’ve ever seen stick out of the holes in his woollen socks. A TV hisses in the corner and a smoky iron furnace belts out a bit of welcome heat. With the border crossing complete, we head off once again and pull alongside Lake Karakul some two hours later, the highest lake in Central Asia. At 3,900m, the vista is nothing short of spectacular, the lofty silence only broken by the dark, icy waters lapping the shore. The unexpected sight of a lone bicyclist coming toward us is reason enough to pause. The cyclist pulls up alongside us and introduces himself as Ben from the UK. He looks as exhausted as we surely feel and describes the conditions ahead as “tough.” We realise we aren’t going to cross the 4,600m pass ahead of us before nightfall.

A quick scan of the small dusty village to our west reveals a hand-painted sign that reads ‘home stay’ and, as we look at the towering mountains behind us casting long shadows across the landscape, we quickly make up our minds. The three of us cross the hard ice and at last park in a cramped yard. Inside is a simple room where a low fire sits in a grate waiting to be stoked. We sit around a table sipping on sweet, warm tea and swap information about each other’s upcoming journeys, as night falls outside.

In the morning, a thick layer of frost covers both bikes, making them glisten in the pristine morning air. Straining our eyes, we watch Ben become a speck on the northern horizon as we head south and we begin our own steady climb to the Ak-Baital Pass. We rise from the plains too quickly, without the chance to acclimatise. At 4,000m, waves of nausea hit Lisa along with a pounding head. She’s showing signs of altitude sickness, which is a deadly concern in this remote location. Our fastest way down is up and over so we have to push on. It’s -22C and to our left a seemingly endless fence of wooden posts and barbed wire marks the Chinese border.

Acute mountain sickness

At 4,500m, the switchbacks require more concentration. We’re up on the pegs and riding over ice-encrusted muddy streams and loose rock. The snowdrifts across the track, an addition we could well do without. Even with sunglasses and dark visors, the glare from the snow is painful. This is truly a giant’s playground and we are just specks passing through. It’s a humbling experience. Our progress is halted two miles from the summit, the thinning dark trail we have been following now lost under deep snow.

Lisa is feeling worse and I haven’t told her that her lips are now dark blue and her eyes have the sunken look of the oxygen-deprived. From over my shoulder, the coughs of an ancient Russian 4×4 grabs my attention and I wave it down explaining: “My wife is unwell!” Without question, the driver agrees to carry Lisa to the top of the pass, leaving me with the two bikes. I ride mine to the top and walk back for Lisa’s. We stop only for the briefest of moments at the summit of the pass to take in the view before riding downwards along dusty roads as the late afternoon rolls by. The reduction in elevation of 1,000m has improved Lisa’s altitude sickness enough that we know we are out of the woods.

The town of Murghab is our chance to feel some welcome warmth. This is the highest town in Tajikistan at 3,700 metres just below the altitude Lisa needs for any kind of overnight stay. Heading down to a little bazaar, we are in search of water and somewhere to exchange dollars for Tajik somoni, the local currency. Dozens of small stalls line a single street. Some are wooden but most are rust-ravaged shipping containers or the rear carcasses of 4×4s. As we walk the bazaar, we see that the few vendors braving the cold stock little more than a ramshackle mix of old clothes and out of date Snickers bars. A lonely bottle of toxic-coloured shampoo sitting on a wooden plank is the highlight of our shopping experience.

Dusty sanctuary on the Silk Road

Murghab’s dusty streets are now two days behind us. We are in the Pamir Mountains proper, riding Tibet-like high plateaus and wide, remote valleys. Bolivia was the last time we’d ridden this high and felt so utterly separated from the rest of the world. The Chinese call this range the Congling Shan or Onion Mountains, and we can see why. We are not riding a single mountain range but rather a labyrinth of layers of differing ranges, each larger than the next. By mid-afternoon, we’re racing a snowstorm across the Alichur Plain that has pushed in from the south. A wall of freezing air and heavy snow threatens to catch us before our route takes a westerly course.

As the afternoon disappears, we summit the Koi-Tezek Pass at 4,297m and are painfully aware at just how cold we’ve become. Our concentration wanders and wanes. On the western side of Khorog, we fill our bikes to the brim with fuel. Our aim is to reach the capital of Tajikistan, Dushanbe, more than 300 miles away by the end of the day but it’s a tall order. By midmorning our definition of what we thought of as mountains is being rewritten.

We slow our pace as much because of the onslaught of twisting blind bends as for the sheer majesty of the landscape around us. We have been skirting the Afghanistan border for two days on the way to Kulyab. Where the Gunt River meets the Panj River, we detour north for 40 miles before again heading west at Rushan. The tar comes and goes whimsically and for the most part we are riding up on the pegs.

To our left, the Panj River flows fast and full, swollen from the first of winter’s heavy snow. On the western bank lies Afghanistan and dozens of tiny settlements that cling impossibly to mountainsides. Local Afghans wave to us as we pass. Dozens of dark painted signs come and go, each marked with a skull and bones to denote a heavily mined area. Finally, we reach Dushanbe and set about collecting our Iranian and Turkmenistan visas.

Police and GPS games

Armed with our visas, we travel into Uzbekistan, and it’s on the outskirts of the city of Samarkand that I’m waved to the side of the road by a traffic policeman who is fumbling with his speed gun. He is doing his best to convince me I was speeding, demanding I pay an instant fine of $50 (£38). He hadn’t even been holding the gun when I’d passed him! Catching the officer off guard, I shake his hand proudly, stating: “I am a policeman in the UK, we are brothers and I have a GPS.” I tap the screen firmly, flicking through the functions, quickly finding the calculator feature and punch in the numbers 6 and 3. With a half-smile, I show my antagonist that my GPS told me I was only doing 63 when I passed him. Suitably impressed, the officer agrees and the fine disappears.

Once in Samarkand, we park up in the heart of the ancient city and sit quietly on the steps of the magnificent Registan. In medieval times, throngs of people would gather in this grand public square for royal proclamations, parades, and executions. It would also have been bustling with travellers and traders from distant lands who, like Lisa and I, were travelling the Silk Route. Perhaps the most famous of all was Marco Polo whose travelogue eBook of the Marvels of the World has enthralled readers for centuries. Sitting in the Registan while slurping down mouthfuls of fresh pomegranate juice, it’s slowly sinking in that we’re experiencing those same marvels of the world ourselves. We can only imagine what the road ahead has in store.

Want to ride the Pamir highway?

The Pamir Highway, or M41, runs through Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan in Central Asia. It is the only continuous route through the mountains, ascending to 4,654m as it summits Ak-Baital Pass, the second-highest international highway in the world. Russian is still widely used and understood, but the Tajik people speak Tajik, a dialect of Persian. The majority of this area stands at over 4,000m so take time to acclimatise to the high altitude. The currency of Tajikistan is the somoni (som). US dollars are easily exchanged in banks and exchange offices. Most transactions in the Pamirs will be in cash.

Visas

UK citizens require a valid passport and visa which must be obtained in advance. A GBAO permit is required for travel to the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast area of the Pamirs. This must be specifically requested in your application. These areas are Khorog, Murghab, Darwaz, Ishkashim, Vanj, Rushan. This permit will be checked at checkpoints on the road and in Khorog and Murghab.

Food and Lodging

Sanitary conditions are basic in rural areas. Be prepared for no hot or running water and primitive (squat) toilets, especially if staying in private homes in villages. The staple diet in the mountains is Pamiri tea (sheer-chai), coffee, vodka, and yak milk, with meals usually consisting of rice, eggs, mutton, and if you’re lucky, freshly made warm bread called non with yak butter. Most villages on the Pamir Highway have homestays. Built in the traditional Pamiri style and constructed of wood with five pillars, a skylight, and richly decorated with carpets, they provide great hospitality and simple but delicious meals. Prices range from £3.50 (no food) to £9.50 per person per night including dinner and breakfast.

Roads and Biking

Distance is deceiving. Allow a minimum of five days to ride from Osh to Dushanbe. The road is partially paved but is mostly unpaved and heavily damaged in places by erosion, earthquakes, and landslides. In spring and early summer, there are risks of roads being blocked by mudslides. In winter, the high passes are closed by snow. The best time to travel is July to October.

Contact Information

Up to date information on visa requirements and travel advice is available at www.gov.uk/foreign-travel-advice. For information about travelling to Tajikistan go to www.tajiktourism.com