Nothing could prepare motorcycle adventurer Ted Hely for what awaited him in north-east Africa…

Sudan isn’t a place anyone really gives much thought. To the average man on the street, it’s just one of those hot and crazy dustbowl places in that ‘country’, Africa. If you’re a little more tuned into current affairs, you’ll have probably heard of a region called Darfur and the ongoing civil war and riots there. Doesn’t exactly sound appealing, does it?

I cooked up my plan to ride from the UK to South Africa not long after coming home from South America in 2008. South America was fantastic but I was hungry for a bigger challenge and Africa fitted the bill perfectly.

If you want to travel overland down the east coast of Africa, you have to cross through Sudan. There is no other choice. The prospect of this fills most travellers with dread owing to the much-publicised events outlined above… I was one of those people.

My journey started in my home town of Birkenhead, England. I was pondering what to do with myself for the coming winter, determined not to suffer another miserable cold, wet affair. After going to a traveller meeting earlier in the year and watching a few talks on Africa, I was hooked on the Idea of conquering this magnificent continent.

I had an old Suzuki DRZ400 in the back of my garage, sitting next to my beloved Africa Twin. I bought it for a bit of greenlaning and commuting but it never really got used as I prefer the big Honda. I even tried selling it, to free up some cash. After committing myself to the Africa trip, I decided that the DRZ just might be the bike for the job. It was cheap, robust and simple – a bit like me!

Determined to stick to my budget, I started scouring eBay for all the goodies I might need; a fuel tank, touring seat, handlebars, etc. Most of the parts I bought were second hand. The luggage racks I made myself and my panniers were 30-year-old ex-army bags. After 18 months of preparation, paperwork, planning and saving, I was finally ready to leave.

After a lazy three-week ride across Europe, a four-day ferry to Egypt and a long ride south to Aswan, Sudan was going to be my first taste of what I considered real Africa. Egypt is a touristic, money-grabbing frenzy that I’d travelled before, so I couldn’t wait to get my Sudanese Visa and get the hell out of there!

To enter Sudan from Egypt requires a 17-hour ferry ride across Lake Nasser, from Aswan in Egypt to the entry port of Wadi Halfa in northern Sudan.

The ferry into Sudan can barely be described; it has to be seen, smelled and experienced first-hand to full appreciate conditions on board. Don’t be tempted to compare this to the average Dover-to-Calais affair. The ferry is used by the Sudanese to import all the goods they can from Egypt, as almost everything is cheaper there. For every passenger there are eight portable televisions, 12 ironing boards, and 47 tins of peaches, along with everything else you can imagine – including the kitchen sink.

On the way down to Sudan, I’d picked up a few other travellers and was now part of a small overland convoy. This always seems to happen when you get travel bottlenecks like ferry crossings. There was Neil, the well-spoken but temperamental Londoner who I’d ridden with from the UK; Craig and Cam, the two plucky New Zealanders we picked up in Venice; Matt and Kim on their RTW who we acquired in Cairo; and Dave and Steph in their rugged Landrover who we found further south in Egypt. As we were all on the same ferry to Sudan, we agreed to start our trip across the desert together. Little did we know how essential our friendship would become.

As cabins are expensive and limited, the vast majority of passengers were crammed on board the ferry together, huddled on deck among the madness. We’re talking boxes and bags piled up six feet high with 350 Sudanese people and a few nervous travellers squeezed in wherever they could fit.

We spent our night on the boat sleeping eight people in a space made for two. Peering out over the Nile, we watched out for the ancient ruins of Abu Simbel and the odd hovering vulture while taking it in turns for toilet runs and overpriced cold Pepsis.

As for the bike, it was muscled onto a decrepit old barge along with bags of rice and flour and jammed up with rocks to stop it wobbling. The DRZ was destined to be towed down the lake a day later. It’s pretty nerve-racking to sail away to a different country, leaving your bike on a barge, maybe never to be seen again…

After a virtually sleepless night, we slowly approached the Sudanese border port of Wadi Halfa and immediately began to feel the effects of the intense African sun. For October, the average temperature is 41c and boy, don’t you know it! Ducking and diving into shade whenever possible, to spare ourselves a roasting, there was little escape from the heat and putting on the riding gear was a deeply unappealing thought. But we still had customs and immigration to deal with before that.

Once off the ferry, we were ushered on to the jetty and started following the crowds to immigration. The half-mile walk up the jetty wearing Motocross boots under the weight of all the bike luggage in the scorching sun nearly killed me. Luckily, the Sudanese officials were super friendly and welcoming and joked with us as they rummaged through our underwear and books. One particular guard took it upon himself to convert us to Islam and warn us of the dangers of masturbation. This was good advice and a refreshing change from my experience in Egypt, where all you get is a snarl or an open hand waiting for a tip.

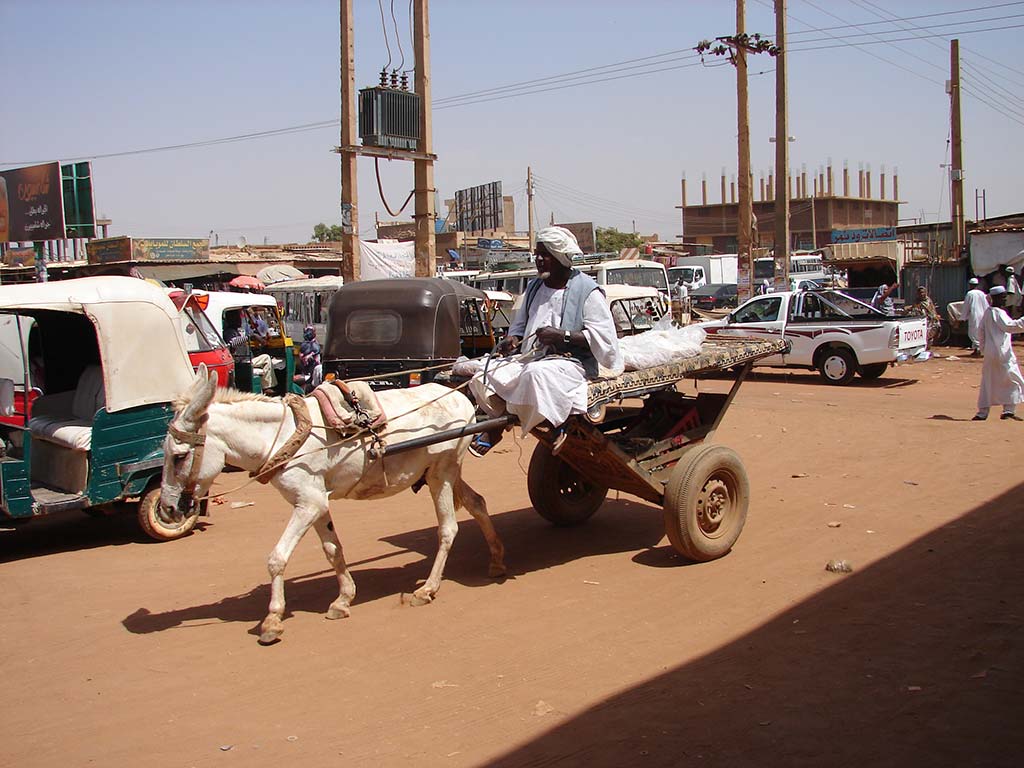

As we all had to wait another day for the barge and our bikes, we took a battered old Landrover taxi into town. This was an experience in itself. The truck was older than me and had clearly never been maintained. The steering wheel was barely connected to the axel and the driver fought with it all the way into town. I lost count of the number of times we nearly came off the road, and he did well not to add two donkeys and a Tuk-Tuk to his daily kill sheet.

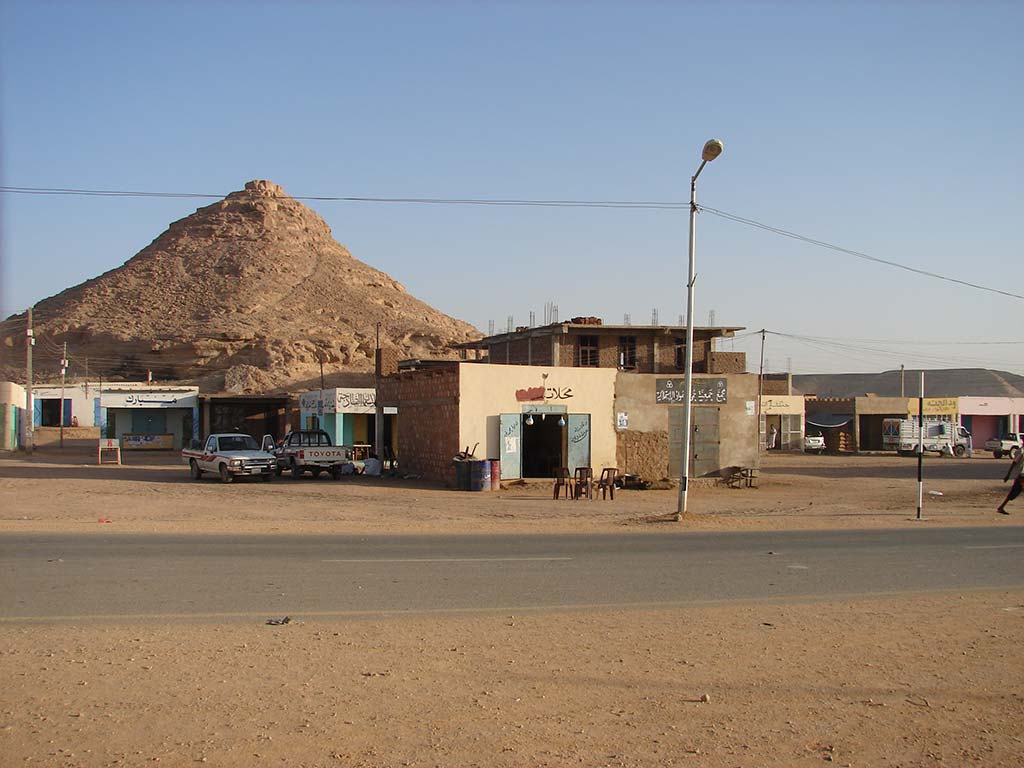

After literally falling out of the Landover, my first experience of Sudan was a bit of a culture shock. Through the mirage of heat and bright sunshine, the main township of Wadi Halfa appeared to be just a small collection of mud brick buildings, corrugated shacks and street sellers surrounded by pyramid-shaped hills. Three-wheedled taxi scooters zipped in and out of the dusty tracks and donkeys stood in the shade, watching the world go by. Groups of Sudanese men gathered around us wearing traditional dress, giving us all very inquisitive looks but friendly welcomes.

We found ourselves a cheap hotel, which was really just four homemade beds in a mud brick room with a light bulb. The outdoor shared toilet was found by following your nose to a hole in the ground which was full of flies and effluence. Holding your breath was necessary to avoid passing out! The washing facilities comprised a bucket of muddy water and a jug. Not the Hilton, but at seven Sudanese pounds (about two quid), you can’t really complain.

Exhausted and sweltering after the last couple of days, we collapsed into our beds for a restless doze. The heat barely dropped after sundown, making for a very uncomfortable night. The local guests who knew better dragged their beds out into the courtyard, to catch a little of the breeze. Too exhausted to follow suit, we suffered on.

The next day was spent messing around with registering our passports and getting our bikes’ carnets stamped. By early afternoon, the barge had arrived, our paperwork was cleared by way of a shady $15 fixer we were finally free to explore Sudan!

The next morning we were all full of excitement and apprehension. There are two southbound roads leaving Wadi: the recently paved but scenic route used by Ewan and Charley on their LWD trip, or the infamous desert railway route. We were determined to conquer the hardest one, so chose the desert route. It’s a gruelling 250-mile stretch of deep sand and rutted tracks. No fuel stops, no water and barely any life. This road is practically deserted apart from some old crumbling train stations. Since work was completed on the paved road, the railway route’s pretty much reverted back to its original desert state, making it even more of an adventure. So off we headed out of town, looking for the exit.

We had convinced ourselves that the railway route couldn’t be as bad as people said. Some travellers even told us it had been recently tarted up. Note to diary: ignore the tourist gossip. Riding out on that deserted track, we really felt like we were putting ourselves into the hands of God and it wasn’t long before we found ourselves knee-deep in sand and the unexpected.

Within five minutes, four out of six bikes had crashed. Wheels were spinning into deep sand; haphazard trails criss-crossing each other, throwing us into even deeper sand. You would stop to help someone pick up their bike just to crash yours two minutes later, and this is how the cycle continued. Pulling the fully laden bikes upright in 45c heat was absolutely exhausting and we were going through fuel and water faster than we expected.

With some forward trail planning and mostly luck, it was possible to ride for about ten minutes before being thrown out of control and into the ground again. As the miles wore on, though, we were slowly getting to grips with the terrain. Even Kim, the least experienced rider of the group, overcame her initial nerves about the deep sand and fought on after multiple crashes. She also refused to give her heavy panniers to the Landrover – respect!

As the miles rolled on, crashes became few and further between and after a while I really got into the spirit of sand riding and started pulling ahead. I felt like Lawrence of Arabia, with nothing but the blazing sun high in the sky and open sand in front of me. I was totally alone and euphoric. I zoned out, concentrating on the sand ahead of me.

After a while, a quick glance behind me confirmed I literally was alone. I jumped off the bike and hid in its shade, waiting for the others to catch up. After 10 minutes I started to worry and decided that I should head back. I had a gut feeling that something had gone wrong. Unfortunately, I was right.

As the others came into sight, I saw everyone huddled together on the ground around a fallen rider. The bent and battered DR650 meant it was either Kim or Matt. I rode over as quickly as possible, praying that it was nothing serious. Kim was lying flat on her back, shaking and obviously in agony. She was conscious, but barely. Her wrist was swollen up and extremely painful. She couldn’t move her leg and her face was bruised and bloodied. She was a right mess. From what Matt said, she had got into a wobble and powered out of it like you should. In a stroke of cruel luck, though, she’d powered herself into a deep rut and ended up cart-wheeling herself over the bike. She went face first over the bars and into the ground, landing hard.

There was no way she could move, let alone ride. Her bike was in bad shape, too. The hard luggage boxes had smashed through her rear wheel, breaking the spokes. Her pannier frame was mangled and her dashboard was in pieces. The bike still started, though, and could be limped back to Wadi Halfa sometime later.

We had to get Kim to a hospital as soon as possible. Trouble was, we were in the middle of the desert! Thank God for Dave and Steph in the Landrover not far behind. Without them, I really don’t know what we would have done. We carefully carried Kim into the Landrover and her bike to a deserted railway station. The New Zealanders realised that they couldn’t do anything to help, so decided to set off alone into the desert and continue their adventure. We agreed to meet up in Khartoum in a few days’ time. Selfishly, I was a little disappointed that I wouldn’t get to ride the road with Craig and Cam, but Matt and Kim had become my good friends over the last few weeks and those of our group who were left were determined to help them in any way we could.

Turning back towards Wadi Halfa, we battled through the same deep sand and ruts as before; this time it was no fun at all. I found it hard to concentrate on riding and had a big crash, hurtling over my handlebars and taking my screen with me. Luckily, I was unhurt.

We eventually got back into Wadi Halfa and headed straight for the police station. Crowds of people gathered round us in the street as we desperately tried to communicate our need for medical help. Eventually, one of the English speaking fixers who’d helped us out the day before appeared and pointed us to the local community hospital where Kim was whisked away.

Neil and I were left to try and sort out Kim’s abandoned bike which was still stuck out in the desert. There’s no recovery service, no emergency services and no auto club in Wadi Halfa. Eventually, the police captain came out to see what all the commotion was about. He spoke good English and offered us the police truck for only the price of the fuel – can you imagine that happening in Western Europe!? I was charged with watching the gear and Neil jumped into the back of the police truck as it disappeared out into the desert, on a mission to collect the bike. An hour later, the bike arrived and off we shot to the medical centre to see Kim.

After an X-ray, a few fainting episodes and a saline drip, Kim was starting to feel a little better. She was in no state to go near a bike (not that hers was fit to be ridden anyway) and she needed a proper doctor. She was discharged from the community hospital with what was thought to be bruising and a badly sprained wrist. She was ordered to rest it for a couple of weeks and take some painkillers. Seeing as there is nothing to do in Wadi Halfa, we decided to ride on to Khartoum. We chucked Kim’s bent and battered DR650 in the back of a rental truck, which was organised by a shady local fixer for $200, and Kim in the back of the Landie with Dave and Steph. Me, Neil and Matt followed suit on the bikes.

After all the madness and commotion of the last few days we were really glad to be out on the open road again. I shouted out a couple of excited “Yeeee-Haaa’!” as we charged out into the desert, leaving Wadi Halfa behind.

Away from the few cities, there is literally nothing but the odd mud brick or straw hut, and maybe a local herding their livestock up and down the roads between them. Occasionally you come across a small town which usually consists of one petrol station, a small shop and some surrounding shacks.

Considering Sudan is in the grip of civil war, you really wouldn’t know it. There are the occasional military checkpoints manned by friendly, waving soldiers and that’s about it. Things are probably a lot more hostile in the south and the east, but as an overland traveller, not once did I feel endangered while on the road or in the cities, even when out alone at night.

The road south to Khartoum cuts straight across the Nubian Desert, covering miles of open country. Endless stretches without horizons, weaving between barren mountain landscapes with the sun beating down. Sudan is a massive country and most of it is desert; it feels infinite.

The minutes turned into hours as I watched my milometer slowly tick along. The road felt especially long on my DRZ. With a comfortable cruising speed of 55- 60mph, it hardly eats up the miles. I found myself cursing it on these long-road days. My backside ached; the hot air chapped my lips and my poor nose took a right scorching as it poked out from under my goggles. Dehydration and fatigue set in fast on rides like this.

The best thing about travelling in a barren desert country is that you can very easily be alone. Once the sun starts coming down, you can pull off the side of the road and venture down any old track to find a place to pitch your tent. You really wouldn’t know that you were five minutes from the main road, apart from the occasional truck horn. As the sun sets in Sudan, the night sky is simply stunning. There is no light pollution in the desert. Constellations and star mist fill the night sky, which is just as well, because there’s nothing else to do but stare up at the darkness in awe. It’s best to delay crawling into your tent for as long as possible, because come bedtime, it’s like a bread oven.

As the days of riding and wild camping rolled on, we finally found ourselves in Khartoum, Sudan’s capital city. From the quiet and empty roads of the desert we were cast into a frenzy of traffic, people and cattle. There were hazards aplenty with gridlocked traffic, mini buses with wheel blades and the occasional strolling donkey. We hadn’t seen traffic like this since Cairo and it left us dazed and confused. The temperature light on my dashboard was glowing manically as my radiators got as hot and bothered as me. The cooling fan had broken in Europe and I was worried about my poor little engine. We ducked and dived between the street sellers and smoking old cars, trying to follow my outdated GPS to the Blue Nile Sailing Club where we’d agreed to meet the rental truck carrying Kim’s broken bike.

After an hour of riding aimlessly up and down city streets we arrived at the sailing club, an old colonial establishment which has sadly fallen into ruin. It’s also the final resting place of Lord Kitchener’s gun boat, which was abandoned there many years ago. It’s the same boat he charged down the Nile on, guns blazing, clearing a path to conquering Sudan for Queen and country. The boat is rusted, rotten and covered in graffiti. It’s such a shame really. It would be a cherished relic back in the UK.

Much to our surprise, the bike was delivered as promised, on time and with no mention of a bribe or tip. Something you get used to in Sudan, the people there are givers, not takers.

Now in Khartoum, our thoughts were put to repairing Kim’s bike and getting her to a hospital for a proper diagnosis. We were accosted by a friendly local guy at the traffic lights (something we’d come to expect). He told us he was a fellow overlander and insisted that we follow him to his friend’s workshop where we would be properly looked after. Once there, we were introduced to Mr Abdul Salaam (aka Mr President), owner of Farbest Autos. Over the next few days, Mr President arranged for us to stay in a luxury apartment just up the road from his workshop where all the repairs to Kim’s bike were carried out. Kim was also taken to hospital where her wrist was found to be fractured and then plastered up. The apartment was a nice relaxing treat after the hard days spent crossing the desert and the hot nights wild camping.

On our last night in Khartoum, Mr President took us out for a tour of the city and then back to his house where we met his family. While there, he insisted we play with his hunting rifles and shot guns. We all took turns doing our best Terminator impressions, of course, before being whisked away to his friend’s house where we were treated to dinner and a very rare opportunity to drink special illegally imported gin. This is quite a big deal in a dry, Muslim country and all very hush-hush. It tasted, well, like London dry gin, but after spending so long in a dry country, it didn’t take much to get me merry.

We left the following morning with Kim and the bike fixed, our bodies burnt and dehydrated, and our clothes and luggage full of dust; it was time to head east for the border of Ethiopia and onwards through Africa. As we rode closer towards the border crossing, the scenery changed dramatically. Suddenly there were trees instead of scrubland, grass instead of sand, and camel and goat farming in abundance. On our last wild camp in Sudan, we were accosted by 200 goats and a line of camels while putting up our tents. The herders hopped off their camels, sat down with us and ate my dinner. Apparently, it’s customary!

I will always have such fond memories of the Sudanese people; friendly, welcoming and helpful. Never once did I feel at risk there. The people we met always asked us about our visit, welcomed us to their country and never thought of asking for money for their assistance. If it wasn’t for the unbearable heat, I could have easily stayed in Sudan for a lot longer. Considering Sudan is at war and has so many political problems, it’s a fantastic place and definitely worth a visit.

The Bike

Suzuki DRZ 400-S

Better known as ‘Ole Daisy’. A lightweight and reliable old nail which makes the off-road sections of Africa far less daunting and a great deal more enjoyable. The flipside is that long days on the open road are slow and tiring due to its slow speeds and narrow seat. My biggest regret is not fitting the 28l fuel tank, which is available, and making the gearing even longer.

Who’s Riding?

‘Travelling’ Ted Hely

I’m a 30-year-old average bloke who’s travelled Europe, South America and Africa by motorcycle. When not daydreaming, I can usually be found tinkering with bikes and making cheap wine in my workshop. I’m keen on football, cycling and running, but my main ambition is to avoid growing up for as long as possible and to keep on travelling. I Love red meat, red wine, making obscenely large bonfires and the excitement of planning a new trip. I really hate saving up to do them, though.

Neil

A well-spoken half Spanish Londoner. Neil Loves riding in your blind spot and telling bad-taste jokes. He dislikes anybody bad mouthing his Trangia stove and being without Facebook. A professional architect, building site manager, computer programmer, engineer and sharp shooter, there’s almost nothing Neil can’t advise you on. He plans to return to van driving when he gets home.

Cam

Originally from New Zealand, Cam’s been living in the UK for two years and decided to tour Africa before heading back to New Zealand with his girlfriend. Cam loves anything to do with an engine and farming; usually both at the same time. Cam loves abusing his decrepit Transalp in the desert and dislikes spending money on accommodation if there’s anywhere he can park his tent for free.

Craig

Another New Zealand Engineer hiding out in the UK. Craig loves beer, food and saying “aye” after every sentence. He gets frustrated that no one can understand his broad NZ accent but usually laughs it off with another beer. The easiest going of the group, there’s almost nothing he isn’t up for.

Dave

The quick-witted Brummie Landrover enthusiast. Dave is always first in with a smart comment for every situation and has an almost fathomless patience for unruly and piss-taking bikers. He loves his Landy, his Mrs Steph and tinned pears. He mostly dislikes riders with broken wrists who eat all his chocolate (naming no names!).

Steph

The better half of Dave, also known as ‘Old mother Hubbard’. Fussing over everyone, she won’t see anyone without a hot cup of coffee or a baby wipe. The proper mum of the group, Steph loves everything and dislikes nothing.

Matt

The cocky lad from Watford, Matt has been growing a pet worm in his stomach for the last 3 months making him a bottomless pit at meal times. Matt obviously loves eating and drinking beer (when Kim will let him). Early into their round the world trip, they don’t tend to think past their next day.

Kim

Pretty and petit, you wouldn’t pin her down as a hardy RTW biker. Full of gusto and stubbornness, she will never be outdone by the boys and bounces better than a bag of frogs. Kim loves dancing on the spot and cream cakes but dislikes Matt going out with the communal purse unsupervised.

Transforming My Bike

▲ Change handlebars to Renthal Dakar high bars; stock ones are rubbish.

▲ Remove all the restrictive junk like the PAIR Valve and carb solenoid. A decent exhaust and re-jetting will make it much more responsive, too. (Google 3×3 modification)

▲ An aftermarket seat and a sheepskin is a must. Your bum will still hurt, though.

▲ A much larger tank is required. I bought the 15l Clark but wish I’d bought the 28l Aqualine tank for the long stretches in Africa. I ended up having a jerry can carrier welded up for the back.

▲ Off-road gearing is useless for overlanding. Having a 16T front sprocket stashed away would have helped a lot. Experiment with sprockets before you leave home. I should have!

▲ Lightweight soft luggage and simple racks work best on a small enduro bike. I made my own from scrap metal.

▲ A larger battery from a Honda Fireblade is a good idea. Cut the back out of your battery box and put a strap around it.

Must-See Sudan

➦ The Wadi Halfa to Abu Hamed railway road. A 250 mile old sand road which follows the railway track south You’re guaranteed to crash and cry

➦ When following the Nile south to Abu Dom, go o the trail and find one of many desert hideaways near the river

➦ There are plenty of old temples to stop and visit on the Dongola road

➦ Farbest Autos in Khartoum. Mr. President will make you his guest. He can have anything fixed from luggage racks and bent wheels to fractured wrists

➦ The convergence of the Blue and the White Nile in Khartoum is quite an experience

➦ Check out Lord Kitchener’s old gunboat which has been left to rot at the Blue Nile Sailing Club, also in Khartoum

Ted’s Top Tips for Travelling Sudan

✓ Have provisions for carrying plenty of water, hydration tablets and sun protection. It’s hotter than hot and the temperature barely drops at night. Expect temperatures of 40c +.

✓ Decent fuel is few and far between. A 300 mile fuel range, a fuel filter for the “oil drum” fuel and a bottle of Octane booster will make your visit much less stressful.

✓ Don’t be afraid to wild camp. Follow any track off the road into the desert and enjoy a perfect night sky

✓ Take plenty of US dollars. Western bank/credit cards and even PayPal won’t work in Sudan. Be prepared for great hospitality, warm welcomes and feeling safer than in your own backyard.

✓ Get your visas in advance if possible. Rejections and long waits are common setbacks.

✓ Alcohol is illegal in Sudan, so it’s best to go T-total while staying there. Don’t attempt to sneak in booze unless you’re prepared to risk a big fine.

Need to Know Sudan

The Republic of Sudan is the largest country in Africa and is divided by the River Nile into west and east sides. Formally a British Colony, there is still plenty of British influence in the buildings in Khartoum. Sudan’s history is one of war, conflict and colonisation. This makes Sudan a mixed bunch of religions and personalities.

Photos: Ted Hely